GSOh No! Hunting for Vulnerabilities in VirtualBox Network Offloads

Introduction

The Pwn2Own contest is like Christmas for me. It’s an exciting competition which involves rummaging around to find critical vulnerabilities in the most commonly used (and often the most difficult) software in the world. Back in March, I was preparing to have a pop at the Vancouver contest and had decided to take a break from writing browser fuzzers to try something different: VirtualBox.

Virtualization is an incredibly interesting target. The complexity involved in both emulating hardware devices and passing data safely to real hardware is astounding. And as the mantra goes: where there is complexity, there are bugs.

For Pwn2Own, it was a safe bet to target an emulated component. In my eyes, network hardware emulation seemed like the right (and usual) route to go. I started with a default component: the NAT emulation code in /src/VBox/Devices/Network/DrvNAT.cpp.

At the time, I just wanted to get a feel for the code, so there was no specific methodical approach to this other than scrolling through the file and reading various parts.

During my scrolling adventure, I landed on something that caught my eye:

static DECLCALLBACK(void) drvNATSendWorker(PDRVNAT pThis, PPDMSCATTERGATHER pSgBuf)

{

#if 0 /* Assertion happens often to me after resuming a VM -- no time to investigate this now. */

Assert(pThis->enmLinkState == PDMNETWORKLINKSTATE_UP);

#endif

if (pThis->enmLinkState == PDMNETWORKLINKSTATE_UP)

{

struct mbuf *m = (struct mbuf *)pSgBuf->pvAllocator;

if (m)

{

/*

* A normal frame.

*/

pSgBuf->pvAllocator = NULL;

slirp_input(pThis->pNATState, m, pSgBuf->cbUsed);

}

else

{

/*

* GSO frame, need to segment it.

*/

/** @todo Make the NAT engine grok large frames? Could be more efficient... */

#if 0 /* this is for testing PDMNetGsoCarveSegmentQD. */

uint8_t abHdrScratch[256];

#endif

uint8_t const *pbFrame = (uint8_t const *)pSgBuf->aSegs[0].pvSeg;

PCPDMNETWORKGSO pGso = (PCPDMNETWORKGSO)pSgBuf->pvUser;

uint32_t const cSegs = PDMNetGsoCalcSegmentCount(pGso, pSgBuf->cbUsed); Assert(cSegs > 1);

for (uint32_t iSeg = 0; iSeg pNATState, pGso->cbHdrsTotal + pGso->cbMaxSeg, &pvSeg, &cbSeg);

if (!m)

break;

#if 1

uint32_t cbPayload, cbHdrs;

uint32_t offPayload = PDMNetGsoCarveSegment(pGso, pbFrame, pSgBuf->cbUsed,

iSeg, cSegs, (uint8_t *)pvSeg, &cbHdrs, &cbPayload);

memcpy((uint8_t *)pvSeg + cbHdrs, pbFrame + offPayload, cbPayload);

slirp_input(pThis->pNATState, m, cbPayload + cbHdrs);

#else

...

The function used for sending packets from the guest to the network contained a separate code path for Generic Segmentation Offload (GSO) frames and was using memcpy to combine pieces of data.

The next question was of course “How much of this can I control?” and after going through various code paths and writing a simple Python-based constraint solver for all the limiting factors, the answer was “More than I expected” when using the Paravirtualization Network device called VirtIO.

Paravirtualized Networking

An alternative to fully emulating a device is to use paravirtualization. Unlike full virtualization, in which the guest is entirely unaware that it is a guest, paravirtualization has the guest install drivers that are aware that they are running in a guest machine in order to work with the host to transfer data in a much faster and more efficient manner.

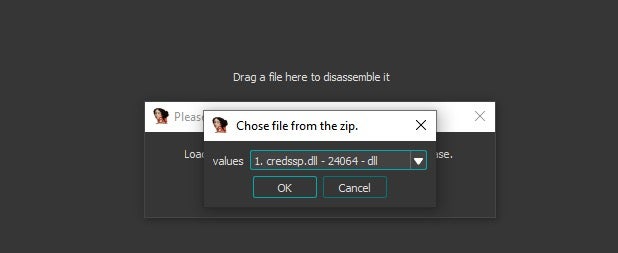

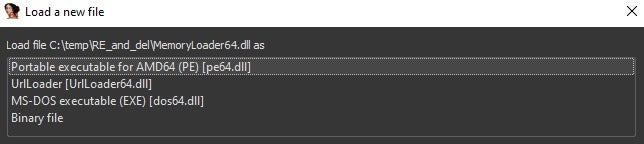

VirtIO is an interface that can be used to develop paravirtualized drivers. One such driver is virtio-net, which comes with the Linux source and is used for networking. VirtualBox, like a number of other virtualization software, supports this as a network adapter:

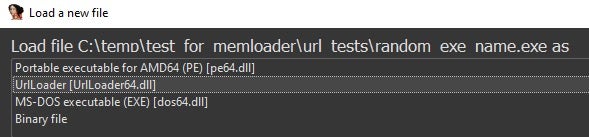

Similarly to the e1000, VirtIO networking works by using ring buffers to transfer data between the guest and the host (In this case called Virtqueues, or VQueues). However, unlike the e1000, VirtIO doesn’t use a single ring with head and tail registers for transmitting but instead uses three separate arrays:

- A Descriptor array that contains the following data per-descriptor:

- Address – The physical address of the data being transferred.

- Length – The length of data at the address.

- Flags – Flags that determine whether the Next field is in-use and whether the buffer is read or write.

- Next – Used when there is chaining.

- An Available ring – An array that contains indexes into the Descriptor array that are in use and can be read by the host.

- A Used ring – An array of indexes into the Descriptor array that have been read by the host.

This looks as so:

When the guest wishes to send packets to the network, it adds an entry to the descriptor table, adds the index of this descriptor to the Available ring, and then increments the Available Index pointer:

Once this is done, the guest ‘kicks’ the host by writing the VQueue index to the Queue Notify register. This triggers the host to begin handling descriptors in the available ring. Once a descriptor has been processed, it is added to the Used ring and the Used Index is incremented:

Generic Segmentation Offload

Next, some background on GSO is required. To understand the need for GSO, it’s important to understand the problem that it solves for network cards.

Originally the CPU would handle all of the heavy lifting when calculating transport layer checksums or segmenting them into smaller ethernet packet sizes. Since this process can be quite slow when dealing with a lot of outgoing network traffic, hardware manufacturers started implementing offloading for these operations, thus removing the strain on the operating system.

For segmentation, this meant that instead of the OS having to pass a number of much smaller packets through the network stack, the OS just passes a single packet once.

It was noticed that this optimization could be applied to other protocols (beyond TCP and UDP) without the need of hardware support by delaying segmentation until just before the network driver receives the message. This resulted in GSO being created.

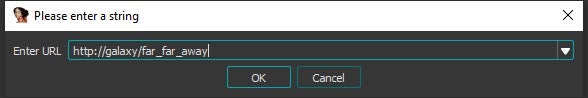

Since VirtIO is a paravirtualized device, the driver is aware that it is in a guest machine and so GSO can be applied between the guest and host. GSO is implemented in VirtIO by adding a context descriptor header to the start of the network buffer. This header can be seen in the following struct:

struct VNetHdr

{

uint8_t u8Flags;

uint8_t u8GSOType;

uint16_t u16HdrLen;

uint16_t u16GSOSize;

uint16_t u16CSumStart;

uint16_t u16CSumOffset;

};

The VirtIO header can be thought of as a similar concept to the Context Descriptor in e1000.

When this header is received, the parameters are verified for some level of validity in vnetR3ReadHeader. Then the function vnetR3SetupGsoCtx is used to fill the standard GSO struct used by VirtualBox across all network devices:

typedef struct PDMNETWORKGSO

{

/** The type of segmentation offloading we're performing (PDMNETWORKGSOTYPE). */

uint8_t u8Type;

/** The total header size. */

uint8_t cbHdrsTotal;

/** The max segment size (MSS) to apply. */

uint16_t cbMaxSeg;

/** Offset of the first header (IPv4 / IPv6). 0 if not not needed. */

uint8_t offHdr1;

/** Offset of the second header (TCP / UDP). 0 if not not needed. */

uint8_t offHdr2;

/** The header size used for segmentation (equal to offHdr2 in UFO). */

uint8_t cbHdrsSeg;

/** Unused. */

uint8_t u8Unused;

} PDMNETWORKGSO;

Once this has been constructed, the VirtIO code creates a scatter-gatherer to assemble the frame from the various descriptors:

/* Assemble a complete frame. */

for (unsigned int i = 1; i 0; i++)

{

unsigned int cbSegment = RT_MIN(uSize, elem.aSegsOut[i].cb);

PDMDevHlpPhysRead(pDevIns, elem.aSegsOut[i].addr,

((uint8_t*)pSgBuf->aSegs[0].pvSeg) + uOffset,

cbSegment);

uOffset += cbSegment;

uSize -= cbSegment;

}

The frame is passed to the NAT code along with the new GSO structure, reaching the point that drew my interest originally.

Vulnerability Analysis

CVE-2021-2145 – Oracle VirtualBox NAT Integer Underflow Privilege Escalation Vulnerability

When the NAT code receives the GSO frame, it gets the full ethernet packet and passes it to Slirp (a library for TCP/IP emulation) as an mbuf message. In order to do this, VirtualBox allocates a new mbuf message and copies the packet to it. The allocation function takes a size and picks the next largest allocation size from three distinct buckets:

- MCLBYTES (0x800 bytes)

- MJUM9BYTES (0x2400 bytes)

- MJUM16BYTES (0x4000 bytes)

struct mbuf *slirp_ext_m_get(PNATState pData, size_t cbMin, void **ppvBuf, size_t *pcbBuf)

{

struct mbuf *m;

int size = MCLBYTES;

LogFlowFunc(("ENTER: cbMin:%d, ppvBuf:%p, pcbBuf:%p\n", cbMin, ppvBuf, pcbBuf));

if (cbMin

If the supplied size is larger than MJUM16BYTES, an assertion is triggered. Unfortunately, this assertion is only compiled when the RT_STRICT macro is used, which is not the case in release builds. This means that execution will continue after this assertion is hit, resulting in a bucket size of 0x800 being selected for the allocation. Since the actual data size is larger, this results in a heap overflow when the user data is copied into the mbuf.

/** @def AssertMsgFailed

* An assertion failed print a message and a hit breakpoint.

*

* @param a printf argument list (in parenthesis).

*/

#ifdef RT_STRICT

# define AssertMsgFailed(a) \

do { \

RTAssertMsg1Weak((const char *)0, __LINE__, __FILE__, RT_GCC_EXTENSION __PRETTY_FUNCTION__); \

RTAssertMsg2Weak a; \

RTAssertPanic(); \

} while (0)

#else

# define AssertMsgFailed(a) do { } while (0)

#endif

CVE-2021-2310 - Oracle VirtualBox NAT Heap-based Buffer Overflow Privilege Escalation Vulnerability

Throughout the code, a function called PDMNetGsoIsValid is used which verifies whether the GSO parameters supplied by the guest are valid. However, whenever it is used it is placed in an assertion. For example:

DECLINLINE(uint32_t) PDMNetGsoCalcSegmentCount(PCPDMNETWORKGSO pGso, size_t cbFrame)

{

size_t cbPayload;

Assert(PDMNetGsoIsValid(pGso, sizeof(*pGso), cbFrame));

cbPayload = cbFrame - pGso->cbHdrsSeg;

return (uint32_t)((cbPayload + pGso->cbMaxSeg - 1) / pGso->cbMaxSeg);

}

As mentioned before, assertions like these are not compiled in the release build. This results in invalid GSO parameters being allowed; a miscalculation can be caused for the size given to slirp_ext_m_get, making it less than the total copied amount by the memcpy in the for-loop. In my proof-of-concept, my parameters for the calculation of pGso->cbHdrsTotal + pGso->cbMaxSeg used for cbMin resulted in an allocation of 0x4000 bytes, but the calculation for cbPayload resulted in a memcpy call for 0x4065 bytes, overflowing the allocated region.

CVE-2021-2442 - Oracle VirtualBox NAT UDP Header Out-of-Bounds

The title of this post makes it seem like GSO is the only vulnerable offload mechanism in place here; however, another offload mechanism is vulnerable too: Checksum Offload.

Checksum offloading can be applied to various protocols that have checksums in their message headers. When emulating, VirtualBox supports this for both TCP and UDP.

In order to access this feature, the GSO frame needs to have the first bit of the u8Flags member set to indicate that the checksum offload is required. In the case of VirtualBox, this bit must always be set since it cannot handle GSO without performing the checksum offload. When VirtualBox handles UDP packets with GSO, it can end up in the function PDMNetGsoCarveSegmentQD in certain circumstances:

case PDMNETWORKGSOTYPE_IPV4_UDP:

if (iSeg == 0)

pdmNetGsoUpdateUdpHdrUfo(RTNetIPv4PseudoChecksum((PRTNETIPV4)&pbFrame[pGso->offHdr1]),

pbSegHdrs, pbFrame, pGso->offHdr2);

The function pdmNetGsoUpdateUdpHdrUfo uses the offHdr2 to indicate where the UDP header is in the packet structure. Eventually this leads to a function called RTNetUDPChecksum:

RTDECL(uint16_t) RTNetUDPChecksum(uint32_t u32Sum, PCRTNETUDP pUdpHdr)

{

bool fOdd;

u32Sum = rtNetIPv4AddUDPChecksum(pUdpHdr, u32Sum);

fOdd = false;

u32Sum = rtNetIPv4AddDataChecksum(pUdpHdr + 1, RT_BE2H_U16(pUdpHdr->uh_ulen) - sizeof(*pUdpHdr), u32Sum, &fOdd);

return rtNetIPv4FinalizeChecksum(u32Sum);

}

This is where the vulnerability is. In this function, the uh_ulen property is completely trusted without any validation, which results in either a size that is outside of the bounds of the buffer, or an integer underflow from the subtraction of sizeof(*pUdpHdr).

rtNetIPv4AddDataChecksum receives both the size value and the packet header pointer and proceeds to calculate the checksum:

/* iterate the data. */

while (cbData > 1)

{

u32Sum += *pw;

pw++;

cbData -= 2;

}

From an exploitation perspective, adding large amounts of out of bounds data together may not seem particularly interesting. However, if the attacker is able to re-allocate the same heap location for consecutive UDP packets with the UDP size parameter being added two bytes at a time, it is possible to calculate the difference in each checksum and disclose the out of bounds data.

On top of this, it’s also possible to use this vulnerability to cause a denial-of-service against other VMs in the network:

Got another Virtualbox vuln fixed (CVE-2021-2442)

Works as both an OOB read in the host process, as well as an integer underflow. In some instances, it can also be used to remotely DoS other Virtualbox VMs! pic.twitter.com/Ir9YQgdZQ7

— maxpl0it (@maxpl0it) August 1, 2021

Outro

Offload support is commonplace in modern network devices so it’s only natural that virtualization software emulating devices does it as well. While most public research has been focused on their main components, such as ring buffers, offloads don’t appear to have had as much scrutiny. Unfortunately in this case I didn’t manage to get an exploit together in time for the Pwn2Own contest, so I ended up reporting the first two to the Zero Day Initiative and the checksum bug to Oracle directly.