An analysis of current and potential kernel security mitigations

Posted by Jann Horn, Project Zero

Introduction

This blog post describes a straightforward Linux kernel locking bug and how I exploited it against Debian Buster's 4.19.0-13-amd64 kernel. Based on that, it explores options for security mitigations that could prevent or hinder exploitation of issues similar to this one.

I hope that stepping through such an exploit and sharing this compiled knowledge with the wider security community can help with reasoning about the relative utility of various mitigation approaches.

A lot of the individual exploitation techniques and mitigation options that I am describing here aren't novel. However, I believe that there is value in writing them up together to show how various mitigations interact with a fairly normal use-after-free exploit.

Our bugtracker entry for this bug, along with the proof of concept, is at https://bugs.chromium.org/p/project-zero/issues/detail?id=2125.

Code snippets in this blog post that are relevant to the exploit are taken from the upstream 4.19.160 release, since that is what the targeted Debian kernel is based on; some other code snippets are from mainline Linux.

(In case you're wondering why the bug and the targeted Debian kernel are from end of last year: I already wrote most of this blogpost around April, but only recently finished it)

I would like to thank Ryan Hileman for a discussion we had a while back about how static analysis might fit into static prevention of security bugs (but note that Ryan hasn't reviewed this post and doesn't necessarily agree with any of my opinions). I also want to thank Kees Cook for providing feedback on an earlier version of this post (again, without implying that he necessarily agrees with everything), and my Project Zero colleagues for reviewing this post and frequent discussions about exploit mitigations.

Background for the bug

On Linux, terminal devices (such as a serial console or a virtual console) are represented by a struct tty_struct. Among other things, this structure contains fields used for the job control features of terminals, which are usually modified using a set of ioctls:

struct tty_struct {

[...]

spinlock_t ctrl_lock;

[...]

struct pid *pgrp; /* Protected by ctrl lock */

struct pid *session;

[...]

struct tty_struct *link;

[...]

}[...];

The pgrp field points to the foreground process group of the terminal (normally modified from userspace via the TIOCSPGRP ioctl); the session field points to the session associated with the terminal. Both of these fields do not point directly to a process/task, but rather to a struct pid. struct pid ties a specific incarnation of a numeric ID to a set of processes that use that ID as their PID (also known in userspace as TID), TGID (also known in userspace as PID), PGID, or SID. You can kind of think of it as a weak reference to a process, although that's not entirely accurate. (There's some extra nuance around struct pid when execve() is called by a non-leader thread, but that's irrelevant here.)

All processes that are running inside a terminal and are subject to its job control refer to that terminal as their "controlling terminal" (stored in ->signal->tty of the process).

A special type of terminal device are pseudoterminals, which are used when you, for example, open a terminal application in a graphical environment or connect to a remote machine via SSH. While other terminal devices are connected to some sort of hardware, both ends of a pseudoterminal are controlled by userspace, and pseudoterminals can be freely created by (unprivileged) userspace. Every time /dev/ptmx (short for "pseudoterminal multiplexor") is opened, the resulting file descriptor represents the device side (referred to in documentation and kernel sources as "the pseudoterminal master") of a new pseudoterminal . You can read from it to get the data that should be printed on the emulated screen, and write to it to emulate keyboard inputs. The corresponding terminal device (to which you'd usually connect a shell) is automatically created by the kernel under /dev/pts/<number>.

One thing that makes pseudoterminals particularly strange is that both ends of the pseudoterminal have their own struct tty_struct, which point to each other using the link member, even though the device side of the pseudoterminal does not have terminal features like job control - so many of its members are unused.

Many of the ioctls for terminal management can be used on both ends of the pseudoterminal; but no matter on which end you call them, they affect the same state, sometimes with minor differences in behavior. For example, in the ioctl handler for TIOCGPGRP:

/**

* tiocgpgrp - get process group

* @tty: tty passed by user

* @real_tty: tty side of the tty passed by the user if a pty else the tty

* @p: returned pid

*

* Obtain the process group of the tty. If there is no process group

* return an error.

*

* Locking: none. Reference to current->signal->tty is safe.

*/

static int tiocgpgrp(struct tty_struct *tty, struct tty_struct *real_tty, pid_t __user *p)

{

struct pid *pid;

int ret;

/*

* (tty == real_tty) is a cheap way of

* testing if the tty is NOT a master pty.

*/

if (tty == real_tty && current->signal->tty != real_tty)

return -ENOTTY;

pid = tty_get_pgrp(real_tty);

ret = put_user(pid_vnr(pid), p);

put_pid(pid);

return ret;

}

As documented in the comment above, these handlers receive a pointer real_tty that points to the normal terminal device; an additional pointer tty is passed in that can be used to figure out on which end of the terminal the ioctl was originally called. As this example illustrates, the tty pointer is normally only used for things like pointer comparisons. In this case, it is used to prevent TIOCGPGRP from working when called on the terminal side by a process which does not have this terminal as its controlling terminal.

Note: If you want to know more about how terminals and job control are intended to work, the book "The Linux Programming Interface" provides a nice introduction to how these older parts of the userspace API are supposed to work. It doesn't describe any of the kernel internals though, since it's written as a reference for userspace programming. And it's from 2010, so it doesn't have anything in it about new APIs that have showed up over the last decade.

The bug

The bug was in the ioctl handler tiocspgrp:

/**

* tiocspgrp - attempt to set process group

* @tty: tty passed by user

* @real_tty: tty side device matching tty passed by user

* @p: pid pointer

*

* Set the process group of the tty to the session passed. Only

* permitted where the tty session is our session.

*

* Locking: RCU, ctrl lock

*/

static int tiocspgrp(struct tty_struct *tty, struct tty_struct *real_tty, pid_t __user *p)

{

struct pid *pgrp;

pid_t pgrp_nr;

[...]

if (get_user(pgrp_nr, p))

return -EFAULT;

[...]

pgrp = find_vpid(pgrp_nr);

[...]

spin_lock_irq(&tty->ctrl_lock);

put_pid(real_tty->pgrp);

real_tty->pgrp = get_pid(pgrp);

spin_unlock_irq(&tty->ctrl_lock);

[...]

}

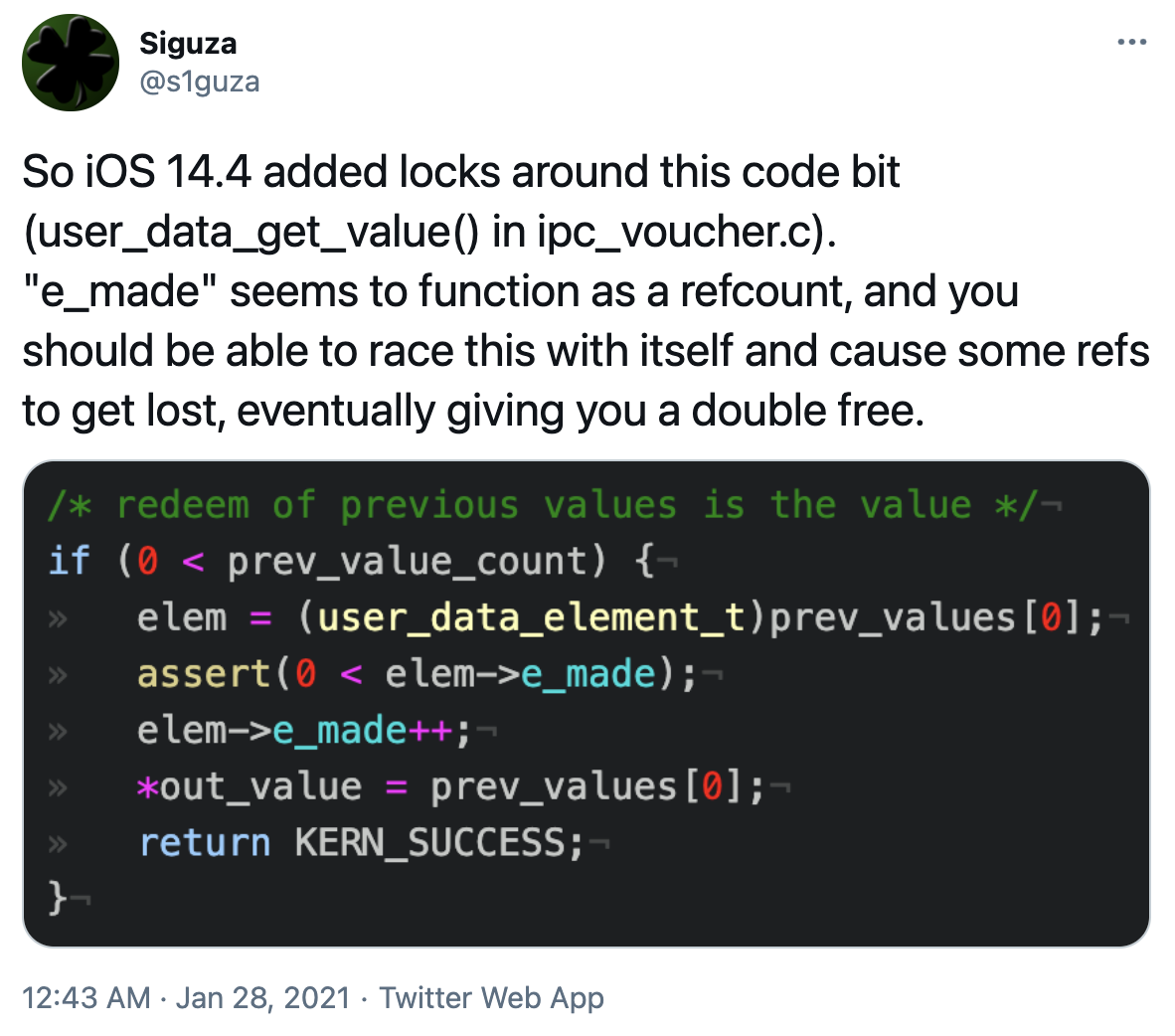

The pgrp member of the terminal side (real_tty) is being modified, and the reference counts of the old and new process group are adjusted accordingly using put_pid and get_pid; but the lock is taken on tty, which can be either end of the pseudoterminal pair, depending on which file descriptor we pass to ioctl(). So by simultaneously calling the TIOCSPGRP ioctl on both sides of the pseudoterminal, we can cause data races between concurrent accesses to the pgrp member. This can cause reference counts to become skewed through the following races:

ioctl(fd1, TIOCSPGRP, pid_A) ioctl(fd2, TIOCSPGRP, pid_B)

spin_lock_irq(...) spin_lock_irq(...)

put_pid(old_pid)

put_pid(old_pid)

real_tty->pgrp = get_pid(A)

real_tty->pgrp = get_pid(B)

spin_unlock_irq(...) spin_unlock_irq(...)

ioctl(fd1, TIOCSPGRP, pid_A) ioctl(fd2, TIOCSPGRP, pid_B)

spin_lock_irq(...) spin_lock_irq(...)

put_pid(old_pid)

put_pid(old_pid)

real_tty->pgrp = get_pid(B)

real_tty->pgrp = get_pid(A)

spin_unlock_irq(...) spin_unlock_irq(...)

In both cases, the refcount of the old struct pid is decremented by 1 too much, and either A's or B's is incremented by 1 too much.

Once you understand the issue, the fix seems relatively obvious:

if (session_of_pgrp(pgrp) != task_session(current))

goto out_unlock;

retval = 0;

- spin_lock_irq(&tty->ctrl_lock);

+ spin_lock_irq(&real_tty->ctrl_lock);

put_pid(real_tty->pgrp);

real_tty->pgrp = get_pid(pgrp);

- spin_unlock_irq(&tty->ctrl_lock);

+ spin_unlock_irq(&real_tty->ctrl_lock);

out_unlock:

rcu_read_unlock();

return retval;

Attack stages

In this section, I will first walk through how my exploit works; afterwards I will discuss different defensive techniques that target these attack stages.

Attack stage: Freeing the object with multiple dangling references

This bug allows us to probabilistically skew the refcount of a struct pid down, depending on which way the race happens: We can run colliding TIOCSPGRP calls from two threads repeatedly, and from time to time that will mess up the refcount. But we don't immediately know how many times the refcount skew has actually happened.

What we'd really want as an attacker is a way to skew the refcount deterministically. We'll have to somehow compensate for our lack of information about whether the refcount was skewed successfully. We could try to somehow make the race deterministic (seems difficult), or after each attempt to skew the refcount assume that the race worked and run the rest of the exploit (since if we didn't skew the refcount, the initial memory corruption is gone, and nothing bad will happen), or we can attempt to find an information leak that lets us figure out the state of the reference count.

On typical desktop/server distributions, the following approach works (unreliably, depending on RAM size) for setting up a freed struct pid with multiple dangling references:

- Allocate a new

struct pid (by creating a new task).

- Create a large number of references to it (by sending messages with

SCM_CREDENTIALS to unix domain sockets, and leaving those messages queued up).

- Repeatedly trigger the

TIOCSPGRP race to skew the reference count downwards, with the number of attempts chosen such that we expect that the resulting refcount skew is bigger than the number of references we need for the rest of our attack, but smaller than the number of extra references we created.

- Let the task owning the

pid exit and die, and wait for RCU (read-copy-update, a mechanism that involves delaying the freeing of some objects) to settle such that the task's reference to the pid is gone. (Waiting for an RCU grace period from userspace is not a primitive that is intentionally exposed through the UAPI, but there are various ways userspace can do it - e.g. by testing when a released BPF program's memory is subtracted from memory accounting, or by abusing the membarrier(MEMBARRIER_CMD_GLOBAL, ...) syscall after the kernel version where RCU flavors were unified.)

- Create a new thread, and let that thread attempt to drop all the references we created.

Because the refcount is smaller at the start of step 5 than the number of references we are about to drop, the pid will be freed at some point during step 5; the next attempt to drop a reference will cause a use-after-free:

struct upid {

int nr;

struct pid_namespace *ns;

};

struct pid

{

atomic_t count;

unsigned int level;

/* lists of tasks that use this pid */

struct hlist_head tasks[PIDTYPE_MAX];

struct rcu_head rcu;

struct upid numbers[1];

};

[...]

void put_pid(struct pid *pid)

{

struct pid_namespace *ns;

if (!pid)

return;

ns = pid->numbers[pid->level].ns;

if ((atomic_read(&pid->count) == 1) ||

atomic_dec_and_test(&pid->count)) {

kmem_cache_free(ns->pid_cachep, pid);

put_pid_ns(ns);

}

}

When the object is freed, the SLUB allocator normally replaces the first 8 bytes (sidenote: a different position is chosen starting in 5.7, see Kees' blog) of the freed object with an XOR-obfuscated freelist pointer; therefore, the count and level fields are now effectively random garbage. This means that the load from pid->numbers[pid->level] will now be at some random offset from the pid, in the range from zero to 64 GiB. As long as the machine doesn't have tons of RAM, this will likely cause a kernel segmentation fault. (Yes, I know, that's an absolutely gross and unreliable way to exploit this. It mostly works though, and I only noticed this issue when I already had the whole thing written, so I didn't really want to go back and change it... plus, did I mention that it mostly works?)

Linux in its default configuration, and the configuration shipped by most general-purpose distributions, attempts to fix up unexpected kernel page faults and other types of "oopses" by killing only the crashing thread. Therefore, this kernel page fault is actually useful for us as a signal: Once the thread has died, we know that the object has been freed, and can continue with the rest of the exploit.

If this code looked a bit differently and we were actually reaching a double-free, the SLUB allocator would also detect that and trigger a kernel oops (see set_freepointer() for the CONFIG_SLAB_FREELIST_HARDENED case).

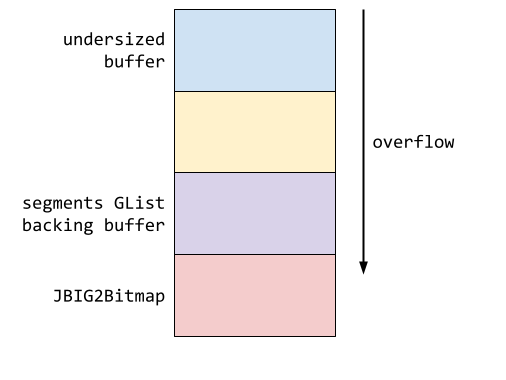

Discarded attack idea: Directly exploiting the UAF at the SLUB level

On the Debian kernel I was looking at, a struct pid in the initial namespace is allocated from the same kmem_cache as struct seq_file and struct epitem - these three slabs have been merged into one by find_mergeable() to reduce memory fragmentation, since their object sizes, alignment requirements, and flags match:

root@deb10:/sys/kernel/slab# ls -l pid

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 0 Feb 6 00:09 pid -> :A-0000128

root@deb10:/sys/kernel/slab# ls -l | grep :A-0000128

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Feb 6 00:09 :A-0000128

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 0 Feb 6 00:09 eventpoll_epi -> :A-0000128

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 0 Feb 6 00:09 pid -> :A-0000128

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 0 Feb 6 00:09 seq_file -> :A-0000128

root@deb10:/sys/kernel/slab#

A straightforward way to exploit a dangling reference to a SLUB object is to reallocate the object through the same kmem_cache it came from, without ever letting the page reach the page allocator. To figure out whether it's easy to exploit this bug this way, I made a table listing which fields appear at each offset in these three data structures (using pahole -E --hex -C <typename> <path to vmlinux debug info>):

| offset |

pid |

eventpoll_epi / epitem (RCU-freed) |

seq_file |

| 0x00 |

count.counter (4) (CONTROL) |

rbn.__rb_parent_color (8) (TARGET?) |

buf (8) (TARGET?) |

| 0x04 |

level (4) |

|

|

| 0x08 |

tasks[PIDTYPE_PID] (8) |

rbn.rb_right (8) / rcu.func (8) |

size (8) |

| 0x10 |

tasks[PIDTYPE_TGID] (8) |

rbn.rb_left (8) |

from (8) |

| 0x18 |

tasks[PIDTYPE_PGID] (8) |

rdllink.next (8) |

count (8) |

| 0x20 |

tasks[PIDTYPE_SID] (8) |

rdllink.prev (8) |

pad_until (8) |

| 0x28 |

rcu.next (8) |

next (8) |

index (8) |

| 0x30 |

rcu.func (8) |

ffd.file (8) |

read_pos (8) |

| 0x38 |

numbers[0].nr (4) |

ffd.fd (4) |

version (8) |

| 0x3c |

[hole] (4) |

nwait (4) |

|

| 0x40 |

numbers[0].ns (8) |

pwqlist.next (8) |

lock (0x20): counter (8) |

| 0x48 |

--- |

pwqlist.prev (8) |

|

| 0x50 |

--- |

ep (8) |

|

| 0x58 |

--- |

fllink.next (8) |

|

| 0x60 |

--- |

fllink.prev (8) |

op (8) |

| 0x68 |

--- |

ws (8) |

poll_event (4) |

| 0x6c |

--- |

|

[hole] (4) |

| 0x70 |

--- |

event.events (4) |

file (8) |

| 0x74 |

--- |

event.data (8) (CONTROL) |

|

| 0x78 |

--- |

|

private (8) (TARGET?) |

| 0x7c |

--- |

--- |

|

| 0x80 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

In this case, reallocating the object as one of those three types didn't seem to me like a nice way forward (although it should be possible to exploit this somehow with some effort, e.g. by using count.counter to corrupt the buf field of seq_file). Also, some systems might be using the slab_nomerge kernel command line flag, which disables this merging behavior.

Another approach that I didn't look into here would have been to try to corrupt the obfuscated SLUB freelist pointer (obfuscation is implemented in freelist_ptr()); but since that stores the pointer in big-endian, count.counter would only effectively let us corrupt the more significant half of the pointer, which would probably be a pain to exploit.

Attack stage: Freeing the object's page to the page allocator

This section will refer to some internals of the SLUB allocator; if you aren't familiar with those, you may want to at least look at slides 2-4 and 13-14 of Christoph Lameter's slab allocator overview talk from 2014. (Note that that talk covers three different allocators; the SLUB allocator is what most systems use nowadays.)

The alternative to exploiting the UAF at the SLUB allocator level is to flush the page out to the page allocator (also called the buddy allocator), which is the last level of dynamic memory allocation on Linux (once the system is far enough into the boot process that the memblock allocator is no longer used). From there, the page can theoretically end up in pretty much any context. We can flush the page out to the page allocator with the following steps:

- Instruct the kernel to pin our task to a single CPU. Both SLUB and the page allocator use per-cpu structures; so if the kernel migrates us to a different CPU in the middle, we would fail.

- Before allocating the victim

struct pid whose refcount will be corrupted, allocate a large number of objects to drain partially-free slab pages of all their unallocated objects. If the victim object (which will be allocated in step 5 below) landed in a page that is already partially used at this point, we wouldn't be able to free that page.

- Allocate around

objs_per_slab * (1+cpu_partial) objects - in other words, a set of objects that completely fill at least cpu_partial pages, where cpu_partial is the maximum length of the "percpu partial list". Those newly allocated pages that are completely filled with objects are not referenced by SLUB's freelists at this point because SLUB only tracks pages with free objects on its freelists.

- Fill

objs_per_slab-1 more objects, such that at the end of this step, the "CPU slab" (the page from which allocations will be served first) will not contain anything other than free space and fresh allocations (created in this step).

- Allocate the victim object (a

struct pid). The victim page (the page from which the victim object came) will usually be the CPU slab from step 4, but if step 4 completely filled the CPU slab, the victim page might also be a new, freshly allocated CPU slab.

- Trigger the bug on the victim object to create an uncounted reference, and free the object.

- Allocate

objs_per_slab+1 more objects. After this, the victim page will be completely filled with allocations from steps 4 and 7, and it won't be the CPU slab anymore (because the last allocation can not have fit into the victim page).

- Free all allocations from steps 4 and 7. This causes the victim page to become empty, but does not free the page; the victim page is placed on the percpu partial list once a single object from that page has been freed, and then stays on that list.

- Free one object per page from the allocations from step 3. This adds all these pages to the percpu partial list until it reaches the limit

cpu_partial, at which point it will be flushed: Pages containing some in-use objects are placed on SLUB's per-NUMA-node partial list, and pages that are completely empty are freed back to the page allocator. (We don't free all allocations from step 3 because we only want the victim page to be freed to the page allocator.) Note that this step requires that every objs_per_slab-th object the allocator gave us in step 3 is on a different page.

When the page is given to the page allocator, we benefit from the page being order-0 (4 KiB, native page size): For order-0 pages, the page allocator has special freelists, one per CPU+zone+migratetype combination. Pages on these freelists are not normally accessed from other CPUs, and they don't immediately get combined with adjacent free pages to form higher-order free pages.

At this point we are able to perform use-after-free accesses to some offset inside the free victim page, using codepaths that interpret part of the victim page as a struct pid. Note that at this point, we still don't know exactly at which offset inside the victim page the victim object is located.

Attack stage: Reallocating the victim page as a pagetable

At the point where the victim page has reached the page allocator's freelist, it's essentially game over - at this point, the page can be reused as anything in the system, giving us a broad range of options for exploitation. In my opinion, most defences that act after we've reached this point are fairly unreliable.

One type of allocation that is directly served from the page allocator and has nice properties for exploitation are page tables (which have also been used to exploit Rowhammer). One way to abuse the ability to modify a page table would be to enable the read/write bit in a page table entry (PTE) that maps a file page to which we are only supposed to have read access - for example, this could be used to gain write access to part of a setuid binary's .text segment and overwrite it with malicious code.

We don't know at which offset inside the victim page the victim object is located; but since a page table is effectively an array of 8-byte-aligned elements of size 8 and the victim object's alignment is a multiple of that, as long as we spray all elements of the victim array, we don't need to know the victim object's offset.

To allocate a page table full of PTEs mapping the same file page, we have to:

- prepare by setting up a 2MiB-aligned memory region (because each last-level page table describes 2MiB of virtual memory) containing single-page

mmap() mappings of the same file page (meaning each mapping corresponds to one PTE); then

- trigger allocation of the page table and fill it with PTEs by reading from each mapping

struct pid has the same alignment as a PTE, and it starts with a 32-bit refcount, so that refcount is guaranteed to overlap the first half of a PTE, which is 64-bit. Because X86 CPUs are little-endian, incrementing the refcount field in the freed struct pid increments the least significant half of the PTE - so it effectively increments the PTE. (Except for the edge case where the least significant half is 0xffffffff, but that's not the case here.)

struct pid: count | level | tasks[0] | tasks[1] | tasks[2] | ...

pagetable: PTE | PTE | PTE | PTE | ...

Therefore we can increment one of the PTEs by repeatedly triggering get_pid(), which tries to increment the refcount of the freed object. This can be turned into the ability to write to the file page as follows:

- Increment the PTE by 0x42 to set the Read/Write bit and the Dirty bit. (If we didn't set the Dirty bit, the CPU would do it by itself when we write to the corresponding virtual address, so we could also just increment by 0x2 here.)

- For each mapping, attempt to overwrite its contents with malicious data and ignore page faults.

- This might throw spurious errors because of outdated TLB entries, but taking a page fault will automatically evict such TLB entries, so if we just attempt the write twice, this can't happen on the second write (modulo CPU migration, as mentioned above).

- One easy way to ignore page faults is to let the kernel perform the memory write using

pread(), which will return -EFAULT on fault.

If the kernel notices the Dirty bit later on, that might trigger writeback, which could crash the kernel if the mapping isn't set up for writing. Therefore, we have to reset the Dirty bit. We can't reliably decrement the PTE because put_pid() inefficiently accesses pid->numbers[pid->level] even when the refcount isn't dropping to zero, but we can increment it by an additional 0x80-0x42=0x3e, which means the final value of the PTE, compared to the initial value, will just have the additional bit 0x80 set, which the kernel ignores.

Afterwards, we launch the setuid executable (which, in the version in the pagecache, now contains the code we injected), and gain root privileges:

user@deb10:~/tiocspgrp$ make

as -o rootshell.o rootshell.S

ld -o rootshell rootshell.o --nmagic

gcc -Wall -o poc poc.c

user@deb10:~/tiocspgrp$ ./poc

starting up...

executing in first level child process, setting up session and PTY pair...

setting up unix sockets for ucreds spam...

draining pcpu and node partial pages

preparing for flushing pcpu partial pages

launching child process

child is 1448

ucreds spam done, struct pid refcount should be lifted. starting to skew refcount...

refcount should now be skewed, child exiting

child exited cleanly

waiting for RCU call...

bpf load with rlim 0x0: -1 (Operation not permitted)

bpf load with rlim 0x1000: 452 (Success)

bpf load success with rlim 0x1000: got fd 452

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

RCU callbacks executed

gonna try to free the pid...

double-free child died with signal 9 after dropping 9990 references (99%)

hopefully reallocated as an L1 pagetable now

PTE forcibly marked WRITE | DIRTY (hopefully)

clobber via corrupted PTE succeeded in page 0, 128-byte-allocation index 3, returned 856

clobber via corrupted PTE succeeded in page 0, 128-byte-allocation index 3, returned 856

bash: cannot set terminal process group (1447): Inappropriate ioctl for device

bash: no job control in this shell

root@deb10:/home/user/tiocspgrp# id

uid=0(root) gid=1000(user) groups=1000(user),24(cdrom),25(floppy),27(sudo),29(audio),30(dip),44(video),46(plugdev),108(netdev),112(lpadmin),113(scanner),120(wireshark)

root@deb10:/home/user/tiocspgrp#

Note that nothing in this whole exploit requires us to leak any kernel-virtual or physical addresses, partly because we have an increment primitive instead of a plain write; and it also doesn't involve directly influencing the instruction pointer.

Defence

This section describes different ways in which this exploit could perhaps have been prevented from working. To assist the reader, the titles of some of the subsections refer back to specific exploit stages from the section above.

Against bugs being reachable: Attack surface reduction

A potential first line of defense against many kernel security issues is to only make kernel subsystems available to code that needs access to them. If an attacker does not have direct access to a vulnerable subsystem and doesn't have sufficient influence over a system component with access to make it trigger the issue, the issue is effectively unexploitable from the attacker's security context.

Pseudoterminals are (more or less) only necessary for interactively serving users who have shell access (or something resembling that), including:

- terminal emulators inside graphical user sessions

- SSH servers

screen sessions started from various types of terminals

Things like webservers or phone apps won't normally need access to such devices; but there are exceptions. For example:

- a web server is used to provide a remote root shell for system administration

- a phone app's purpose is to make a shell available to the user

- a shell script uses

expect to interact with a binary that requires a terminal for input/output

In my opinion, the biggest limits on attack surface reduction as a defensive strategy are:

- It exposes a workaround to an implementation concern of the kernel (potential memory safety issues) in user-facing API, which can lead to compatibility issues and maintenance overhead - for example, from a security standpoint, I think it might be a good idea to require phone apps and systemd services to declare their intention to use the PTY subsystem at install time, but that would be an API change requiring some sort of action from application authors, creating friction that wouldn't be necessary if we were confident that the kernel is working properly. This might get especially messy in the case of software that invokes external binaries depending on configuration, e.g. a web server that needs PTY access when it is used for server administration. (This is somewhat less complicated when a benign-but-potentially-exploitable application actively applies restrictions to itself; but not every application author is necessarily willing to design a fine-grained sandbox for their code, and even then, there may be compatibility issues caused by libraries outside the application author's control.)

- It can't protect a subsystem from a context that fundamentally needs access to it. (E.g. Android's

/dev/binder is directly accessible by Chrome renderers on Android because they have Android code running inside them.)

- It means that decisions that ought to not influence the security of a system (making an API that does not grant extra privileges available to some potentially-untrusted context) essentially involve a security tradeoff.

Still, in practice, I believe that attack surface reduction mechanisms (especially seccomp) are currently some of the most important defense mechanisms on Linux.

Against bugs in source code: Compile-time locking validation

The bug in TIOCSPGRP was a fairly straightforward violation of a straightforward locking rule: While a tty_struct is live, accessing its pgrp member is forbidden unless the ctrl_lock of the same tty_struct is held. This rule is sufficiently simple that it wouldn't be entirely unreasonable to expect the compiler to be able to verify it - as long as you somehow inform the compiler about this rule, because figuring out the intended locking rules just from looking at a piece of code can often be hard even for humans (especially when some of the code is incorrect).

When you are starting a new project from scratch, the overall best way to approach this is to use a memory-safe language - in other words, a language that has explicitly been designed such that the programmer has to provide the compiler with enough information about intended memory safety semantics that the compiler can automatically verify them. But for existing codebases, it might be worth looking into how much of this can be retrofitted.

Clang's Thread Safety Analysis feature does something vaguely like what we'd need to verify the locking in this situation:

$ nl -ba -s' ' thread-safety-test.cpp | sed 's|^ ||'

1 struct __attribute__((capability("mutex"))) mutex {

2 };

3

4 void lock_mutex(struct mutex *p) __attribute__((acquire_capability(*p)));

5 void unlock_mutex(struct mutex *p) __attribute__((release_capability(*p)));

6

7 struct foo {

8 int a __attribute__((guarded_by(mutex)));

9 struct mutex mutex;

10 };

11

12 int good(struct foo *p1, struct foo *p2) {

13 lock_mutex(&p1->mutex);

14 int result = p1->a;

15 unlock_mutex(&p1->mutex);

16 return result;

17 }

18

19 int bogus(struct foo *p1, struct foo *p2) {

20 lock_mutex(&p1->mutex);

21 int result = p2->a;

22 unlock_mutex(&p1->mutex);

23 return result;

24 }

$ clang++ -c -o thread-safety-test.o thread-safety-test.cpp -Wall -Wthread-safety

thread-safety-test.cpp:21:22: warning: reading variable 'a' requires holding mutex 'p2->mutex' [-Wthread-safety-precise]

int result = p2->a;

^

thread-safety-test.cpp:21:22: note: found near match 'p1->mutex'

1 warning generated.

$

However, this does not currently work when compiling as C code because the guarded_by attribute can't find the other struct member; it seems to have been designed mostly for use in C++ code. A more fundamental problem is that it also doesn't appear to have built-in support for distinguishing the different rules for accessing a struct member depending on the lifetime state of the object. For example, almost all objects with locked members will have initialization/destruction functions that have exclusive access to the entire object and can access members without locking. (The lock might not even be initialized in those states.)

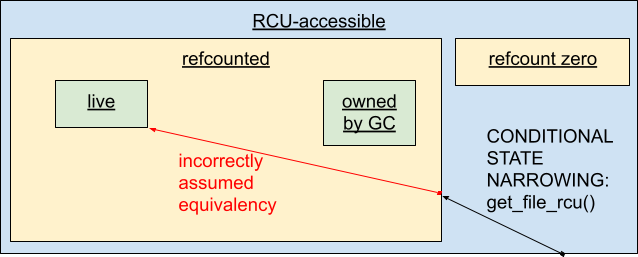

Some objects also have more lifetime states; in particular, for many objects with RCU-managed lifetime, only a subset of the members may be accessed through an RCU reference without having upgraded the reference to a refcounted one beforehand. Perhaps this could be addressed by introducing a new type attribute that can be used to mark pointers to structs in special lifetime states? (For C++ code, Clang's Thread Safety Analysis simply disables all checks in all constructor/destructor functions.)

I am hopeful that, with some extensions, something vaguely like Clang's Thread Safety Analysis could be used to retrofit some level of compile-time safety against unintended data races. This will require adding a lot of annotations, in particular to headers, to document intended locking semantics; but such annotations are probably anyway necessary to enable productive work on a complex codebase. In my experience, when there are no detailed comments/annotations on locking rules, every attempt to change a piece of code you're not intimately familiar with (without introducing horrible memory safety bugs) turns into a foray into the thicket of the surrounding call graphs, trying to unravel the intentions behind the code.

The one big downside is that this requires getting the development community for the codebase on board with the idea of backfilling and maintaining such annotations. And someone has to write the analysis tooling that can verify the annotations.

At the moment, the Linux kernel does have some very coarse locking validation via sparse; but this infrastructure is not capable of detecting situations where the wrong lock is used or validating that a struct member is protected by a lock. It also can't properly deal with things like conditional locking, which makes it hard to use for anything other than spinlocks/RCU. The kernel's runtime locking validation via LOCKDEP is more advanced, but mostly with a focus on locking correctness of RCU pointers as well as deadlock detection (the main focus); again, there is no mechanism to, for example,automatically validate that a given struct member is only accessed under a specific lock (which would probably also be quite costly to implement with runtime validation). Also, as a runtime validation mechanism, it can't discover errors in code that isn't executed during testing (although it can combine separately observed behavior into race scenarios without ever actually observing the race).

Against bugs in source code: Global static locking analysis

An alternative approach to checking memory safety rules at compile time is to do it either after the entire codebase has been compiled, or with an external tool that analyzes the entire codebase. This allows the analysis tooling to perform analysis across compilation units, reducing the amount of information that needs to be made explicit in headers. This may be a more viable approach if peppering annotations everywhere across headers isn't viable; but it also reduces the utility to human readers of the code, unless the inferred semantics are made visible to them through some special code viewer. It might also be less ergonomic in the long run if changes to one part of the kernel could make the verification of other parts fail - especially if those failures only show up in some configurations.

I think global static analysis is probably a good tool for finding some subsets of bugs, and it might also help with finding the worst-case depth of kernel stacks or proving the absence of deadlocks, but it's probably less suited for proving memory safety correctness?

Against exploit primitives: Attack primitive reduction via syscall restrictions

(Yes, I made up that name because I thought that capturing this under "Attack surface reduction" is too muddy.)

Because allocator fastpaths (both in SLUB and in the page allocator) are implemented using per-CPU data structures, the ease and reliability of exploits that want to coax the kernel's memory allocators into reallocating memory in specific ways can be improved if the attacker has fine-grained control over the assignment of exploit threads to CPU cores. I'm calling such a capability, which provides a way to facilitate exploitation by influencing relevant system state/behavior, an "attack primitive" here. Luckily for us, Linux allows tasks to pin themselves to specific CPU cores without requiring any privilege using the sched_setaffinity() syscall.

(As a different example, one primitive that can provide an attacker with fairly powerful capabilities is being able to indefinitely stall kernel faults on userspace addresses via FUSE or userfaultfd.)

Just like in the section "Attack surface reduction" above, an attacker's ability to use these primitives can be reduced by filtering syscalls; but while the mechanism and the compatibility concerns are similar, the rest is fairly different:

Attack primitive reduction does not normally reliably prevent a bug from being exploited; and an attacker will sometimes even be able to obtain a similar but shoddier (more complicated, less reliable, less generic, ...) primitive indirectly, for example:

Attack surface reduction is about limiting access to code that is suspected to contain exploitable bugs; in a codebase written in a memory-unsafe language, that tends to apply to pretty much the entire codebase. Attack surface reduction is often fairly opportunistic: You permit the things you need, and deny the rest by default.

Attack primitive reduction limits access to code that is suspected or known to provide (sometimes very specific) exploitation primitives. For example, one might decide to specifically forbid access to FUSE and userfaultfd for most code because of their utility for kernel exploitation, and, if one of those interfaces is truly needed, design a workaround that avoids exposing the attack primitive to userspace. This is different from attack surface reduction, where it often makes sense to permit access to any feature that a legitimate workload wants to use.

A nice example of an attack primitive reduction is the sysctl vm.unprivileged_userfaultfd, which was first introduced so that userfaultfd can be made completely inaccessible to normal users and was then later adjusted so that users can be granted access to part of its functionality without gaining the dangerous attack primitive. (But if you can create unprivileged user namespaces, you can still use FUSE to get an equivalent effect.)

When maintaining lists of allowed syscalls for a sandboxed system component, or something along those lines, it may be a good idea to explicitly track which syscalls are explicitly forbidden for attack primitive reduction reasons, or similarly strong reasons - otherwise one might accidentally end up permitting them in the future. (I guess that's kind of similar to issues that one can run into when maintaining ACLs...)

But like in the previous section, attack primitive reduction also tends to rely on making some functionality unavailable, and so it might not be viable in all situations. For example, newer versions of Android deliberately indirectly give apps access to FUSE through the AppFuse mechanism. (That API doesn't actually give an app direct access to /dev/fuse, but it does forward read/write requests to the app.)

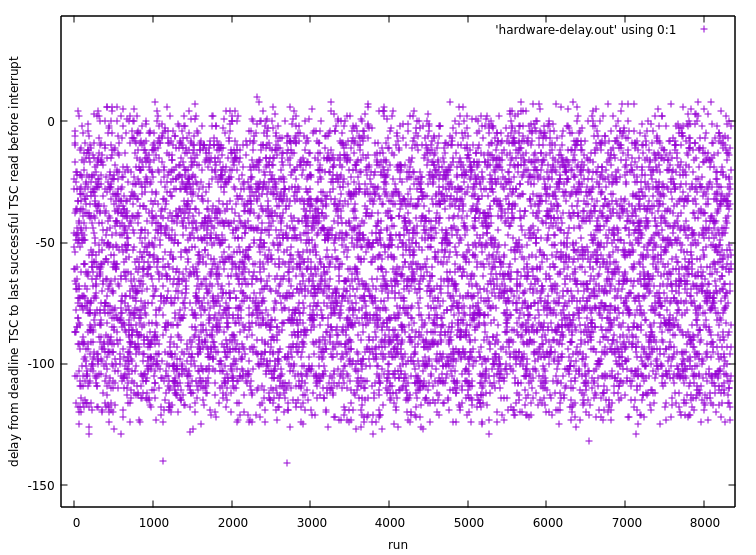

Against oops-based oracles: Lockout or panic on crash

The ability to recover from kernel oopses in an exploit can help an attacker compensate for a lack of information about system state. Under some circumstances, it can even serve as a binary oracle that can be used to more or less perform a binary search for a value, or something like that.

(It used to be even worse on some distributions, where dmesg was accessible for unprivileged users; so if you managed to trigger an oops or WARN, you could then grab the register states at all IRET frames in the kernel stack, which could be used to leak things like kernel pointers. Luckily nowadays most distributions, including Ubuntu 20.10, restrict dmesg access.)

Android and Chrome OS nowadays set the kernel's panic_on_oops flag, meaning the machine will immediately restart when a kernel oops happens. This makes it hard to use oopsing as part of an exploit, and arguably also makes more sense from a reliability standpoint - the system will be down for a bit, and it will lose its existing state, but it will also reset into a known-good state instead of continuing in a potentially half-broken state, especially if the crashing thread was holding mutexes that can never again be released, or things like that. On the other hand, if some service crashes on a desktop system, perhaps that shouldn't cause the whole system to immediately go down and make you lose unsaved state - so panic_on_oops might be too drastic there.

A good solution to this might require a more fine-grained approach. (For example, grsecurity has for a long time had the ability to lock out specific UIDs that have caused crashes.) Perhaps it would make sense to allow the init daemon to use different policies for crashes in different services/sessions/UIDs?

Against UAF access: Deterministic UAF mitigation

One defense that would reliably stop an exploit for this issue would be a deterministic use-after-free mitigation. Such a mitigation would reliably protect the memory formerly occupied by the object from accesses through dangling pointers to the object, at least once the memory has been reused for a different purpose (including reuse to store heap metadata). For write operations, this probably requires either atomicity of the access check and the actual write or an RCU-like delayed freeing mechanism. For simple read operations, it can also be implemented by ordering the access check after the read, but before the read value is used.

A big downside of this approach on its own is that extra checks on every memory access will probably come with an extremely high efficiency penalty, especially if the mitigation can not make any assumptions about what kinds of parallel accesses might be happening to an object, or what semantics pointers have. (The proof-of-concept implementation I presented at LSSNA 2020 (slides, recording) had CPU overhead roughly in the range 60%-159% in kernel-heavy benchmarks, and ~8% for a very userspace-heavy benchmark.)

Unfortunately, even a deterministic use-after-free mitigation often won't be enough to deterministically limit the blast radius of something like a refcounting mistake to the object in which it occurred. Consider a case where two codepaths concurrently operate on the same object: Codepath A assumes that the object is live and subject to normal locking rules. Codepath B knows that the reference count reached zero, assumes that it therefore has exclusive access to the object (meaning all members are mutable without any locking requirements), and is trying to tear down the object. Codepath B might then start dropping references the object was holding on other objects while codepath A is following the same references. This could then lead to use-after-frees on pointed-to objects. If all data structures are subject to the same mitigation, this might not be too much of a problem; but if some data structures (like struct page) are not protected, it might permit a mitigation bypass.

Similar issues apply to data structures with union members that are used in different object states; for example, here's some random kernel data structure with an rcu_head in a union (just a random example, there isn't anything wrong with this code as far as I know):

struct allowedips_node {

struct wg_peer __rcu *peer;

struct allowedips_node __rcu *bit[2];

/* While it may seem scandalous that we waste space for v4,

* we're alloc'ing to the nearest power of 2 anyway, so this

* doesn't actually make a difference.

*/

u8 bits[16] __aligned(__alignof(u64));

u8 cidr, bit_at_a, bit_at_b, bitlen;

/* Keep rarely used list at bottom to be beyond cache line. */

union {

struct list_head peer_list;

struct rcu_head rcu;

};

};

As long as everything is working properly, the peer_list member is only used while the object is live, and the rcu member is only used after the object has been scheduled for delayed freeing; so this code is completely fine. But if a bug somehow caused the peer_list to be read after the rcu member has been initialized, type confusion would result.

In my opinion, this demonstrates that while UAF mitigations do have a lot of value (and would have reliably prevented exploitation of this specific bug), a use-after-free is just one possible consequence of the symptom class "object state confusion" (which may or may not be the same as the bug class of the root cause). It would be even better to enforce rules on object states, and ensure that an object e.g. can't be accessed through a "refcounted" reference anymore after the refcount has reached zero and has logically transitioned into a state like "non-RCU members are exclusively owned by thread performing teardown" or "RCU callback pending, non-RCU members are uninitialized" or "exclusive access to RCU-protected members granted to thread performing teardown, other members are uninitialized". Of course, doing this as a runtime mitigation would be even costlier and messier than a reliable UAF mitigation; this level of protection is probably only realistic with at least some level of annotations and static validation.

Against UAF access: Probabilistic UAF mitigation; pointer leaks

Summary: Some types of probabilistic UAF mitigation break if the attacker can leak information about pointer values; and information about pointer values easily leaks to userspace, e.g. through pointer comparisons in map/set-like structures.

If a deterministic UAF mitigation is too costly, an alternative is to do it probabilistically; for example, by tagging pointers with a small number of bits that are checked against object metadata on access, and then changing that object metadata when objects are freed.

The downside of this approach is that information leaks can be used to break the protection. One example of a type of information leak that I'd like to highlight (without any judgment on the relative importance of this compared to other types of information leaks) are intentional pointer comparisons, which have quite a few facets.

A relatively straightforward example where this could be an issue is the kcmp() syscall. This syscall compares two kernel objects using an arithmetic comparison of their permuted pointers (using a per-boot randomized permutation, see kptr_obfuscate()) and returns the result of the comparison (smaller, equal or greater). This gives userspace a way to order handles to kernel objects (e.g. file descriptors) based on the identities of those kernel objects (e.g. struct file instances), which in turn allows userspace to group a set of such handles by backing kernel object in O(n*log(n)) time using a standard sorting algorithm.

This syscall can be abused for improving the reliability of use-after-free exploits against some struct types because it checks whether two pointers to kernel objects are equal without accessing those objects: An attacker can allocate an object, somehow create a reference to the object that is not counted properly, free the object, reallocate it, and then verify whether the reallocation indeed reused the same address by comparing the dangling reference and a reference to the new object with kcmp(). If kcmp() includes the pointer's tag bits in the comparison, this would likely also permit breaking probabilistic UAF mitigations.

Essentially the same concern applies when a kernel pointer is encrypted and then given to userspace in fuse_lock_owner_id(), which encrypts the pointer to a files_struct with an open-coded version of XTEA before passing it to a FUSE daemon.

In both these cases, explicitly stripping tag bits would be an acceptable workaround because a pointer without tag bits still uniquely identifies a memory location; and given that these are very special interfaces that intentionally expose some degree of information about kernel pointers to userspace, it would be reasonable to adjust this code manually.

A somewhat more interesting example is the behavior of this piece of userspace code:

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <sys/epoll.h>

#include <sys/eventfd.h>

#include <sys/resource.h>

#include <err.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sched.h>

#define SYSCHK(x) ({ \

typeof(x) __res = (x); \

if (__res == (typeof(x))-1) \

err(1, "SYSCHK(" #x ")"); \

__res; \

})

int main(void) {

struct rlimit rlim;

SYSCHK(getrlimit(RLIMIT_NOFILE, &rlim));

rlim.rlim_cur = rlim.rlim_max;

SYSCHK(setrlimit(RLIMIT_NOFILE, &rlim));

cpu_set_t cpuset;

CPU_ZERO(&cpuset);

CPU_SET(0, &cpuset);

SYSCHK(sched_setaffinity(0, sizeof(cpuset), &cpuset));

int epfd = SYSCHK(epoll_create1(0));

for (int i=0; i<1000; i++)

SYSCHK(eventfd(0, 0));

for (int i=0; i<192; i++) {

int fd = SYSCHK(eventfd(0, 0));

struct epoll_event event = {

.events = EPOLLIN,

.data = { .u64 = i }

};

SYSCHK(epoll_ctl(epfd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, fd, &event));

}

char cmd[100];

sprintf(cmd, "cat /proc/%d/fdinfo/%d", getpid(), epfd);

system(cmd);

}

It first creates a ton of eventfds that aren't used. Then it creates a bunch more eventfds and creates epoll watches for them, in creation order, with a monotonically incrementing counter in the "data" field. Afterwards, it asks the kernel to print the current state of the epoll instance, which comes with a list of all registered epoll watches, including the value of the data member (in hex). But how is this list sorted? Here's the result of running that code in a Ubuntu 20.10 VM (truncated, because it's a bit long):

user@ubuntuvm:~/epoll_fdinfo$ ./epoll_fdinfo

pos: 0

flags: 02

mnt_id: 14

tfd: 1040 events: 19 data: 24 pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1050 events: 19 data: 2e pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1024 events: 19 data: 14 pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1029 events: 19 data: 19 pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1048 events: 19 data: 2c pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1042 events: 19 data: 26 pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1026 events: 19 data: 16 pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

tfd: 1033 events: 19 data: 1d pos:0 ino:2f9a sdev:d

[...]

The data: field here is the loop index we stored in the .data member, formatted as hex. Here is the complete list of the data values in decimal:

36, 46, 20, 25, 44, 38, 22, 29, 30, 45, 33, 28, 41, 31, 23, 37, 24, 50, 32, 26, 21, 43, 35, 48, 27, 39, 40, 47, 42, 34, 49, 19, 95, 105, 111, 84, 103, 97, 113, 88, 89, 104, 92, 87, 100, 90, 114, 96, 83, 109, 91, 85, 112, 102, 94, 107, 86, 98, 99, 106, 101, 93, 108, 110, 12, 1, 14, 5, 6, 9, 4, 17, 7, 13, 0, 8, 2, 11, 3, 15, 16, 18, 10, 135, 145, 119, 124, 143, 137, 121, 128, 129, 144, 132, 127, 140, 130, 122, 136, 123, 117, 131, 125, 120, 142, 134, 115, 126, 138, 139, 146, 141, 133, 116, 118, 66, 76, 82, 55, 74, 68, 52, 59, 60, 75, 63, 58, 71, 61, 53, 67, 54, 80, 62, 56, 51, 73, 65, 78, 57, 69, 70, 77, 72, 64, 79, 81, 177, 155, 161, 166, 153, 147, 163, 170, 171, 154, 174, 169, 150, 172, 164, 178, 165, 159, 173, 167, 162, 152, 176, 157, 168, 148, 149, 156, 151, 175, 158, 160, 186, 188, 179, 180, 183, 191, 181, 187, 182, 185, 189, 190, 184

While these look sort of random, you can see that the list can be split into blocks of length 32 that consist of shuffled contiguous sequences of numbers:

Block 1 (32 values in range 19-50):

36, 46, 20, 25, 44, 38, 22, 29, 30, 45, 33, 28, 41, 31, 23, 37, 24, 50, 32, 26, 21, 43, 35, 48, 27, 39, 40, 47, 42, 34, 49, 19

Block 2 (32 values in range 83-114):

95, 105, 111, 84, 103, 97, 113, 88, 89, 104, 92, 87, 100, 90, 114, 96, 83, 109, 91, 85, 112, 102, 94, 107, 86, 98, 99, 106, 101, 93, 108, 110

Block 3 (19 values in range 0-18):

12, 1, 14, 5, 6, 9, 4, 17, 7, 13, 0, 8, 2, 11, 3, 15, 16, 18, 10

Block 4 (32 values in range 115-146):

135, 145, 119, 124, 143, 137, 121, 128, 129, 144, 132, 127, 140, 130, 122, 136, 123, 117, 131, 125, 120, 142, 134, 115, 126, 138, 139, 146, 141, 133, 116, 118

Block 5 (32 values in range 51-82):

66, 76, 82, 55, 74, 68, 52, 59, 60, 75, 63, 58, 71, 61, 53, 67, 54, 80, 62, 56, 51, 73, 65, 78, 57, 69, 70, 77, 72, 64, 79, 81

Block 6 (32 values in range 147-178):

177, 155, 161, 166, 153, 147, 163, 170, 171, 154, 174, 169, 150, 172, 164, 178, 165, 159, 173, 167, 162, 152, 176, 157, 168, 148, 149, 156, 151, 175, 158, 160

Block 7 (13 values in range 179-191):

186, 188, 179, 180, 183, 191, 181, 187, 182, 185, 189, 190, 184

What's going on here becomes clear when you look at the data structures epoll uses internally. ep_insert calls ep_rbtree_insert to insert a struct epitem into a red-black tree (a type of sorted binary tree); and this red-black tree is sorted using a tuple of a struct file * and a file descriptor number:

/* Compare RB tree keys */

static inline int ep_cmp_ffd(struct epoll_filefd *p1,

struct epoll_filefd *p2)

{

return (p1->file > p2->file ? +1:

(p1->file < p2->file ? -1 : p1->fd - p2->fd));

}

So the values we're seeing have been ordered based on the virtual address of the corresponding struct file; and SLUB allocates struct file from order-1 pages (i.e. pages of size 8 KiB), which can hold 32 objects each:

root@ubuntuvm:/sys/kernel/slab/filp# cat order

1

root@ubuntuvm:/sys/kernel/slab/filp# cat objs_per_slab

32

root@ubuntuvm:/sys/kernel/slab/filp#

This explains the grouping of the numbers we saw: Each block of 32 contiguous values corresponds to an order-1 page that was previously empty and is used by SLUB to allocate objects until it becomes full.

With that knowledge, we can transform those numbers a bit, to show the order in which objects were allocated inside each page (excluding pages for which we haven't seen all allocations):

$ cat slub_demo.py

#!/usr/bin/env python3

blocks = [

[ 36, 46, 20, 25, 44, 38, 22, 29, 30, 45, 33, 28, 41, 31, 23, 37, 24, 50, 32, 26, 21, 43, 35, 48, 27, 39, 40, 47, 42, 34, 49, 19 ],

[ 95, 105, 111, 84, 103, 97, 113, 88, 89, 104, 92, 87, 100, 90, 114, 96, 83, 109, 91, 85, 112, 102, 94, 107, 86, 98, 99, 106, 101, 93, 108, 110 ],

[ 12, 1, 14, 5, 6, 9, 4, 17, 7, 13, 0, 8, 2, 11, 3, 15, 16, 18, 10 ],

[ 135, 145, 119, 124, 143, 137, 121, 128, 129, 144, 132, 127, 140, 130, 122, 136, 123, 117, 131, 125, 120, 142, 134, 115, 126, 138, 139, 146, 141, 133, 116, 118 ],

[ 66, 76, 82, 55, 74, 68, 52, 59, 60, 75, 63, 58, 71, 61, 53, 67, 54, 80, 62, 56, 51, 73, 65, 78, 57, 69, 70, 77, 72, 64, 79, 81 ],

[ 177, 155, 161, 166, 153, 147, 163, 170, 171, 154, 174, 169, 150, 172, 164, 178, 165, 159, 173, 167, 162, 152, 176, 157, 168, 148, 149, 156, 151, 175, 158, 160 ],

[ 186, 188, 179, 180, 183, 191, 181, 187, 182, 185, 189, 190, 184 ]

]

for alloc_indices in blocks:

if len(alloc_indices) != 32:

continue

# indices of allocations ('data'), sorted by memory location, shifted to be relative to the block

alloc_indices_relative = [position - min(alloc_indices) for position in alloc_indices]

# reverse mapping: memory locations of allocations,

# sorted by index of allocation ('data').

# if we've observed all allocations in a page,

# these will really be indices into the page.

memory_location_by_index = [alloc_indices_relative.index(idx) for idx in range(0, len(alloc_indices))]

print(memory_location_by_index)

$ ./slub_demo.py

[31, 2, 20, 6, 14, 16, 3, 19, 24, 11, 7, 8, 13, 18, 10, 29, 22, 0, 15, 5, 25, 26, 12, 28, 21, 4, 9, 1, 27, 23, 30, 17]

[16, 3, 19, 24, 11, 7, 8, 13, 18, 10, 29, 22, 0, 15, 5, 25, 26, 12, 28, 21, 4, 9, 1, 27, 23, 30, 17, 31, 2, 20, 6, 14]

[23, 30, 17, 31, 2, 20, 6, 14, 16, 3, 19, 24, 11, 7, 8, 13, 18, 10, 29, 22, 0, 15, 5, 25, 26, 12, 28, 21, 4, 9, 1, 27]

[20, 6, 14, 16, 3, 19, 24, 11, 7, 8, 13, 18, 10, 29, 22, 0, 15, 5, 25, 26, 12, 28, 21, 4, 9, 1, 27, 23, 30, 17, 31, 2]

[5, 25, 26, 12, 28, 21, 4, 9, 1, 27, 23, 30, 17, 31, 2, 20, 6, 14, 16, 3, 19, 24, 11, 7, 8, 13, 18, 10, 29, 22, 0, 15]

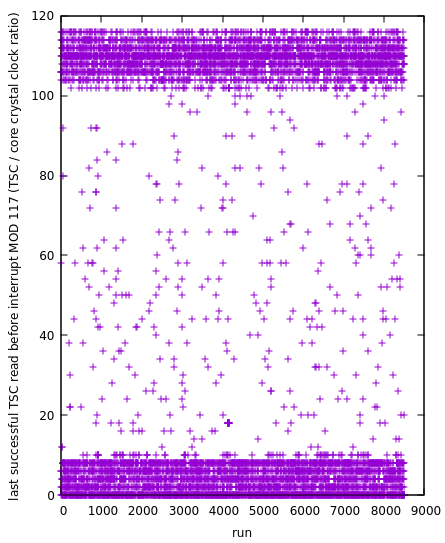

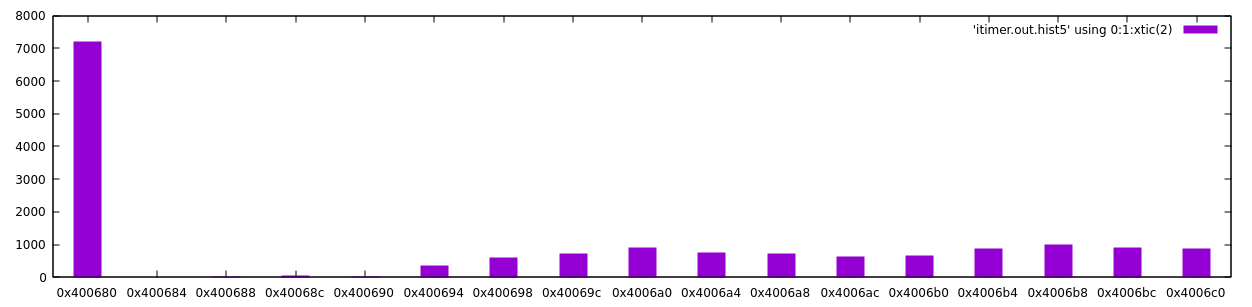

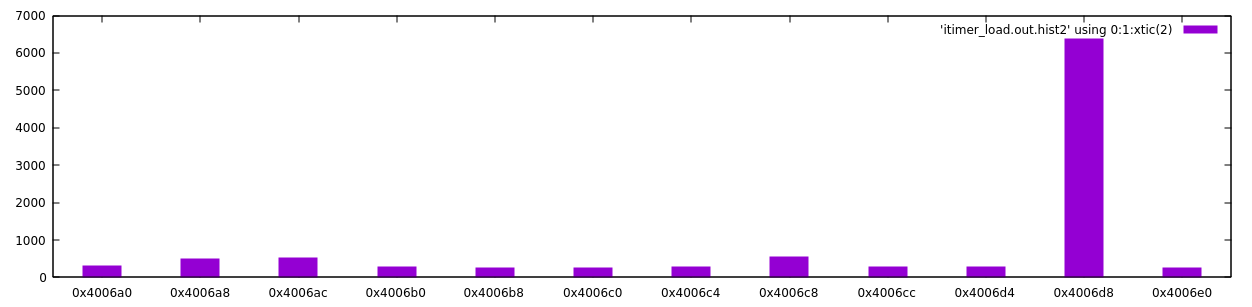

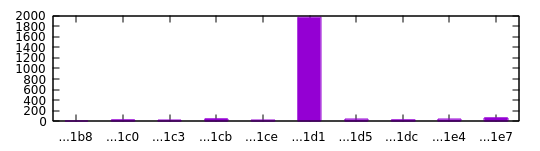

And these sequences are almost the same, except that they have been rotated around by different amounts. This is exactly the SLUB freelist randomization scheme, as introduced in commit 210e7a43fa905!

When a SLUB kmem_cache is created (an instance of the SLUB allocator for a specific size class and potentially other specific attributes, usually initialized at boot time), init_cache_random_seq and cache_random_seq_create fill an array ->random_seq with randomly-ordered object indices via Fisher-Yates shuffle, with the array length equal to the number of objects that fit into a page. Then, whenever SLUB grabs a new page from the lower-level page allocator, it initializes the page freelist using the indices from ->random_seq, starting at a random index in the array (and wrapping around when the end is reached). (I'm ignoring the low-order allocation fallback here.)

So in summary, we can bypass SLUB randomization for the slab from which struct file is allocated because someone used it as a lookup key in a specific type of data structure. This is already fairly undesirable if SLUB randomization is supposed to provide protection against some types of local attacks for all slabs.

The heap-randomization-weakening effect of such data structures is not necessarily limited to cases where elements of the data structure can be listed in-order by userspace: If there was a codepath that iterated through the tree in-order and freed all tree nodes, that could have a similar effect, because the objects would be placed on the allocator's freelist sorted by address, cancelling out the randomization. In addition, you might be able to leak information about iteration order through cache side channels or such.

If we introduce a probabilistic use-after-free mitigation that relies on attackers not being able to learn whether the uppermost bits of an object's address changed after it was reallocated, this data structure could also break that. This case is messier than things like kcmp() because here the address ordering leak stems from a standard data structure.

You may have noticed that some of the examples I'm using here would be more or less limited to cases where an attacker is reallocating memory with the same type as the old allocation, while a typical use-after-free attack ends up replacing an object with a differently-typed one to cause type confusion. As an example of a bug that can be exploited for privilege escalation without type confusion at the C structure level, see entry 808 in our bugtracker. My exploit for that bug first starts a writev() operation on a writable file, lets the kernel validate that the file is indeed writable, then replaces the struct file with a read-only file pointing to /etc/crontab, and lets writev() continue. This allows gaining root privileges through a use-after-free bug without having to mess around with kernel pointers, data structure layouts, ROP, or anything like that. Of course that approach doesn't work with every use-after-free though.

(By the way: For an example of pointer leaks through container data structures in a JavaScript engine, see this bug I reported to Firefox back in 2016, when I wasn't a Google employee, which leaks the low 32 bits of a pointer by timing operations on pessimal hash tables - basically turning the HashDoS attack into an infoleak. Of course, nowadays, a side-channel-based pointer leak in a JS engine would probably not be worth treating as a security bug anymore, since you can probably get the same result with Spectre...)

Against freeing SLUB pages: Preventing virtual address reuse beyond the slab

(Also discussed a little bit on the kernel-hardening list in this thread.)

A weaker but less CPU-intensive alternative to trying to provide complete use-after-free protection for individual objects would be to ensure that virtual addresses that have been used for slab memory are never reused outside the slab, but that physical pages can still be reused. This would be the same basic approach as used by PartitionAlloc and others. In kernel terms, that would essentially mean serving SLUB allocations from vmalloc space.

Some challenges I can think of with this approach are:

- SLUB allocations are currently served from the linear mapping, which normally uses hugepages; if vmalloc mappings with 4K PTEs were used instead, TLB pressure might increase, which might lead to some performance degradation.

- To be able to use SLUB allocations in contexts that operate directly on physical memory, it is sometimes necessary for SLUB pages to be physically contiguous. That's not really a problem, but it is different from default vmalloc behavior. (Sidenote: DMA buffers don't always have to be physically contiguous - if you have an IOMMU, you can use that to map discontiguous pages to a contiguous DMA address range, just like how normal page tables create virtually-contiguous memory. See this kernel-internal API for an example that makes use of this, and Fuchsia's documentation for a high-level overview of how all this works in general.)

- Some parts of the kernel convert back and forth between virtual addresses,

struct page pointers, and (for interaction with hardware) physical addresses. This is a relatively straightforward mapping for addresses in the linear mapping, but would become a bit more complicated for vmalloc addresses. In particular, page_to_virt() and phys_to_virt() would have to be adjusted.

- This is probably also going to be an issue for things like Memory Tagging, since pointer tags will have to be reconstructed when converting back to a virtual address. Perhaps it would make sense to forbid these helpers outside low-level memory management, and change existing users to instead keep a normal pointer to the allocation around? Or maybe you could let pointers to

struct page carry the tag bits for the corresponding virtual address in unused/ignored address bits?

The probability that this defense can prevent UAFs from leading to exploitable type confusion depends somewhat on the granularity of slabs; if specific struct types have their own slabs, it provides more protection than if objects are only grouped by size. So to improve the utility of virtually-backed slab memory, it would be necessary to replace the generic kmalloc slabs (which contain various objects, grouped only by size) with ones that are segregated by type and/or allocation site. (The grsecurity/PaX folks have vaguely alluded to doing something roughly along these lines using compiler instrumentation.)

After reallocation as pagetable: Structure layout randomization

Memory safety issues are often exploited in a way that involves creating a type confusion; e.g. exploiting a use-after-free by replacing the freed object with a new object of a different type.

A defense that first appeared in grsecurity/PaX is to shuffle the order of struct members at build time to make it harder to exploit type confusions involving structs; the upstream Linux version of this is in scripts/gcc-plugins/randomize_layout_plugin.c.

How effective this is depends partly on whether the attacker is forced to exploit the issue as a confusion between two structs, or whether the attacker can instead exploit it as a confusion between a struct and an array (e.g. containing characters, pointers or PTEs). Especially if only a single struct member is accessed, a struct-array confusion might still be viable by spraying the entire array with identical elements. Against the type confusion described in this blogpost (between struct pid and page table entries), structure layout randomization could still be somewhat effective, since the reference count is half the size of a PTE and therefore can randomly be placed to overlap either the lower or the upper half of a PTE. (Except that the upstream Linux version of randstruct only randomizes explicitly-marked structs or structs containing only function pointers, and struct pid has no such marking.)

Of course, drawing a clear distinction between structs and arrays oversimplifies things a bit; for example, there might be struct types that have a large number of pointers of the same type or attacker-controlled values, not unlike an array.

If the attacker can not completely sidestep structure layout randomization by spraying the entire struct, the level of protection depends on how kernel builds are distributed:

- If the builds are created centrally by one vendor and distributed to a large number of users, an attacker who wants to be able to compromise users of this vendor would have to rework their exploit to use a different type confusion for each release, which may force the attacker to rewrite significant chunks of the exploit.

- If the kernel is individually built per machine (or similar), and the kernel image is kept secret, an attacker who wants to reliably exploit a target system may be forced to somehow leak information about some structure layouts and either prepare exploits for many different possible struct layouts in advance or write parts of the exploit interactively after leaking information from the target system.

To maximize the benefit of structure layout randomization in an environment where kernels are built centrally by a distribution/vendor, it would be necessary to make randomization a boot-time process by making structure offsets relocatable. (Or install-time, but that would break code signing.) Doing this cleanly (for example, such that 8-bit and 16-bit immediate displacements can still be used for struct member access where possible) would probably require a lot of fiddling with compiler internals, from the C frontend all the way to the emission of relocations. A somewhat hacky version of this approach already exists for C->BPF compilation as BPF CO-RE, using the clang builtin __builtin_preserve_access_index, but that relies on debuginfo, which probably isn't a very clean approach.

Potential issues with structure layout randomization are:

- If structures are hand-crafted to be particularly cache-efficient, fully randomizing structure layout could worsen cache behavior. The existing randstruct implementation optionally avoids this by trying to randomize only within a cache line.

- Unless the randomization is applied in a way that is reflected in DWARF debug info and such (which it isn't in the existing GCC-based implementation), it can make debugging and introspection harder.

- It can break code that makes assumptions about structure layout; but such code is gross and should be cleaned up anyway (and Gustavo Silva has been working on fixing some of those issues).

While structure layout randomization by itself is limited in its effectiveness by struct-array confusions, it might be more reliable in combination with limited heap partitioning: If the heap is partitioned such that only struct-struct confusion is possible, and structure layout randomization makes struct-struct confusion difficult to exploit, and no struct in the same heap partition has array-like properties, then it would probably become much harder to directly exploit a UAF as type confusion. On the other hand, if the heap is already partitioned like that, it might make more sense to go all the way with heap partitioning and create one partition per type instead of dealing with all the hassle of structure layout randomization.

(By the way, if structure layouts are randomized, padding should probably also be randomized explicitly instead of always being on the same side to maximally randomize structure members with low alignment; see my list post on this topic for details.)

Control Flow Integrity

I want to explicitly point out that kernel Control Flow Integrity would have had no impact at all on this exploit strategy. By using a data-only strategy, we avoid having to leak addresses, avoid having to find ROP gadgets for a specific kernel build, and are completely unaffected by any defenses that attempt to protect kernel code or kernel control flow. Things like getting access to arbitrary files, increasing the privileges of a process, and so on don't require kernel instruction pointer control.

Like in my last blogpost on Linux kernel exploitation (which was about a buggy subsystem that an Android vendor added to their downstream kernel), to me, a data-only approach to exploitation feels very natural and seems less messy than trying to hijack control flow anyway.

Maybe things are different for userspace code; but for attacks by userspace against the kernel, I don't currently see a lot of utility in CFI because it typically only affects one of many possible methods for exploiting a bug. (Although of course there could be specific cases where a bug can only be exploited by hijacking control flow, e.g. if a type confusion only permits overwriting a function pointer and none of the permitted callees make assumptions about input types or privileges that could be broken by changing the function pointer.)

Making important data readonly

A defense idea that has shown up in a bunch of places (including Samsung phone kernels and XNU kernels for iOS) is to make data that is crucial to kernel security read-only except when it is intentionally being written to - the idea being that even if an attacker has an arbitrary memory write, they should not be able to directly overwrite specific pieces of data that are of exceptionally high importance to system security, such as credential structures, page tables, or (on iOS, using PPL) userspace code pages.

The problem I see with this approach is that a large portion of the things a kernel does are, in some way, critical to the correct functioning of the system and system security. MMU state management, task scheduling, memory allocation, filesystems, page cache, IPC, ... - if any one of these parts of the kernel is corrupted sufficiently badly, an attacker will probably be able to gain access to all user data on the system, or use that corruption to feed bogus inputs into one of the subsystems whose own data structures are read-only.

In my view, instead of trying to split out the most critical parts of the kernel and run them in a context with higher privileges, it might be more productive to go in the opposite direction and try to approximate something like a proper microkernel: Split out drivers that don't strictly need to be in the kernel and run them in a lower-privileged context that interacts with the core kernel through proper APIs. Of course that's easier said than done! But Linux does already have APIs for safely accessing PCI devices (VFIO) and USB devices from userspace, although userspace drivers aren't exactly its main usecase.

(One might also consider making page tables read-only not because of their importance to system integrity, but because the structure of page table entries makes them nicer to work with in exploits that are constrained in what modifications they can make to memory. I dislike this approach because I think it has no clear conclusion and it is highly invasive regarding how data structures can be laid out.)

Conclusion

This was essentially a boring locking bug in some random kernel subsystem that, if it wasn't for memory unsafety, shouldn't really have much of a relevance to system security. I wrote a fairly straightforward, unexciting (and admittedly unreliable) exploit against this bug; and probably the biggest challenge I encountered when trying to exploit it on Debian was to properly understand how the SLUB allocator works.

My intent in describing the exploit stages, and how different mitigations might affect them, is to highlight that the further a memory corruption exploit progresses, the more options an attacker gains; and so as a general rule, the earlier an exploit is stopped, the more reliable the defense is. Therefore, even if defenses that stop an exploit at an earlier point have higher overhead, they might still be more useful.

I think that the current situation of software security could be dramatically improved - in a world where a little bug in some random kernel subsystem can lead to a full system compromise, the kernel can't provide reliable security isolation. Security engineers should be able to focus on things like buggy permission checks and core memory management correctness, and not have to spend their time dealing with issues in code that ought to not have any relevance to system security.

In the short term, there are some band-aid mitigations that could be used to improve the situation - like heap partitioning or fine-grained UAF mitigation. These might come with some performance cost, and that might make them look unattractive; but I still think that they're a better place to invest development time than things like CFI, which attempts to protect against much later stages of exploitation.

In the long term, I think something has to change about the programming language - plain C is simply too error-prone. Maybe the answer is Rust; or maybe the answer is to introduce enough annotations to C (along the lines of Microsoft's Checked C project, although as far as I can see they mostly focus on things like array bounds rather than temporal issues) to allow Rust-equivalent build-time verification of locking rules, object states, refcounting, void pointer casts, and so on. Or maybe another completely different memory-safe language will become popular in the end, neither C nor Rust?

My hope is that perhaps in the mid-term future, we could have a statically verified, high-performance core of kernel code working together with instrumented, runtime-verified, non-performance-critical legacy code, such that developers can make a tradeoff between investing time into backfilling correct annotations and run-time instrumentation slowdown without compromising on security either way.

TL;DR

memory corruption is a big problem because small bugs even outside security-related code can lead to a complete system compromise; and to address that, it is important that we:

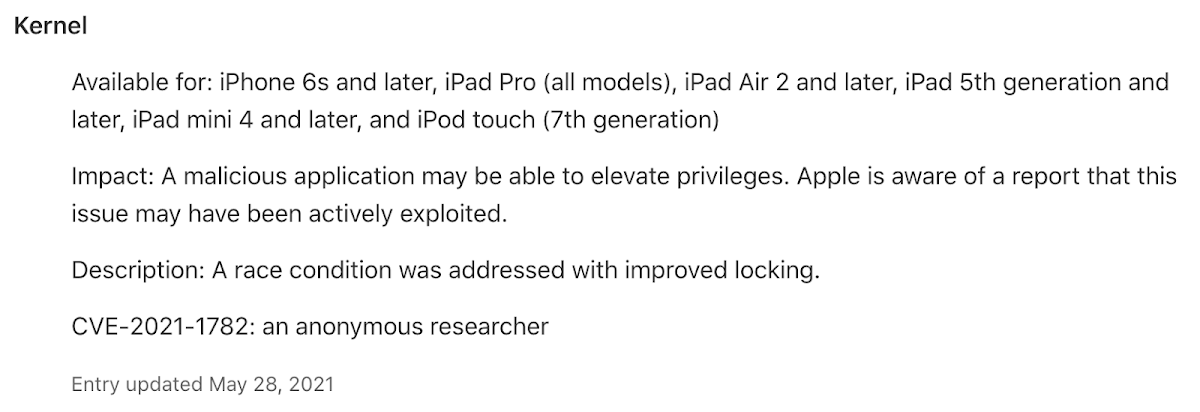

Overview diagram of memory read layout. In the middle is a set of boxes representing the native 4KiB pages being read. All the boxes are contained within a single larger region which is the large page size. Above the boxes are arrows which show that from the base of the 4KiB box a 32KiB read will be made into the file which can satisfy the reads from other 4KiB pages. The final box shows that the last 32KiB of the large page size will always be read as a single page regardless of where in the box the read occurs." style="max-height: 750; max-width: 600;" />

Overview diagram of memory read layout. In the middle is a set of boxes representing the native 4KiB pages being read. All the boxes are contained within a single larger region which is the large page size. Above the boxes are arrows which show that from the base of the 4KiB box a 32KiB read will be made into the file which can satisfy the reads from other 4KiB pages. The final box shows that the last 32KiB of the large page size will always be read as a single page regardless of where in the box the read occurs." style="max-height: 750; max-width: 600;" />